Introduction and Necessary Disclaimer

This one of a series of posts concerning the Authors Guild v. Hathitrust case, specifically these posts take the form of commentary on the Authors Guild Appeal Brief (February 25, 2013). Although I am one of the authors of the Digital Humanities and Law Scholars Amicus Brief, the views expressed on this site are purely my own. My comments on the Authors Guild’s Appeal Brief will not be comprehensive, rather, my aim is to review the aspects of the brief that I found interesting.

Today’s topic …

Not everything is the same as everything else

Legal argument is art of analogizing and distinguishing, drawing out the implications of things already decided in ways that suggest the a favorable outcome for matters still in dispute. Thus, in copyright cases it is quite common to read that x (new thing) is the same as/totally different from y (old thing). The Authors Guild’s brief engages in quite a bit of this kind of argument, but mostly without saying so explicitly. In particular, their brief contains three examples of false equivalence that simply don’t add up.

- The Authors Guild implicitly suggests that the defendants’ orphan works project is the same as the Authors Guild’s own proposal to deal with orphan works in Google Book Search Settlement. It isn’t.

- The Authors Guild argues that the defendants’ orphan works project is a substitute for orphan works legislation. It isn’t.

- The Authors Guild brief proceeds as thought library digitization were the same as library photocopying. It isn’t.

The Universities’ Orphan Works Project v. the Google Book Search Settlement

Most of the Authors Guild’s ink is spilt on the universities’ proposed orphan works project (OWP). The idea behind the defendants’ OWP appears to be that out-of-print books published in the U.S. between 1923 and 1963 should be made available for educational use if the rights holders cannot be reasonably be located. The University of Michigan proposed a method to automate the identification of orphan works for this purpose in 2011. However, the exact nature of this particular project is still yet to determined because after the Authors Guild filed suit against the HathiTrust et al, the University of Michigan announced that the OWP would be temporarily suspended. The University of Michigan candidly admitted that the procedures used to identify orphan works had allowed some works to make their way onto the Orphan Works Lists in error.

The Authors Guild Appeal Brief contains the implicit suggestion that the defendants’ OWP is the same as the audacious exploitation of orphan works that the Authors Guild itself proposed under its Settlement Agreement with Google.

It is true that, as noted at page 10 of the Guild’s Appeal Brief, “a mechanism to help resolve the orphan works issue was one of the key aspects of the attempted settlement of the Google Books case”.

It is also undeniable that Judge Chin commented “the establishment of a mechanism for exploiting unclaimed books is a matter better suited for Congress than this Court”. (Authors Guild v. Google, Inc., 770 F. Supp. 2d 666 (S.D.N.Y. 2011))

But Judge Chin was evaluating the fairness of the private settlement between Google and the Authors Guild, he was not commenting on the question of whether the display of any orphan works under any circumstance could be fair use, nor was he reviewing anything remotely like the libraries much more limited orphan works program.

The Authors Guild proceeds as though the modest orphan works program announced by the university defendants is the same in substance as the universal bookstore rejected by the Judge Chin in 2011. (See e.g., Authors Guild, page 10 “Unhappy with Judge Chin’s decision, [University of Michigan] decided to take the law into its own hands by unilaterally initiating its own program.”) This strikes me as false equivalence.

Under the default settings of the now defunct settlement (proposed 2008, amended 2009, rejected 2011) Google would have been allowed to display up to 20% of a non-fiction work to the entire world and to sell books through consumer purchases and institutional subscriptions. Funds from the sale of orphan works were to held by a ‘book rights registry’ for safe keeping and eventual distribution to worthy causes. [Under the original Settlement Agreement, the revenues attributable to orphan or unclaimed works would have flowed in part to the ‘book rights registry’ and in part to registered authors and publishers.]

The details of the OWP that the defendants may or may not eventually undertake are unclear, but their public statements indicate that any such project would be grounded on non-commercial, limited, educational use. Moreover, the settlement would have treated all books whose copyright owners who failed to notify the registry of their interests as orphan works, the University of Michigan is working on a method to reliably determine a much smaller subset of true orphan works.

Whatever it turns out to be, the Universities’ orphan works project will not be the same as the Authors Guild’s own proposal to deal with orphan works in Google Book Search Settlement.

The Universities’ Orphan Works Project v. Orphan Works Legislation

The Authors Guild Appeal Brief also conflates the universities’ OWP with various legislative solutions that have been proposed over the years in relation to the widely recognized orphan works problem. See for example Authors Guild Ap. Br. at page 15 “Despite clear indications by courts and the Copyright Office that the treatment of orphan works should be left to Congress, the Libraries insist that the OWP is legal.” (There is another example on page 10).

Does it really make sense that Congress’ failure to comprehensively or partially legislate a solution to the problem of orphan works means that the use of orphan works is never allowed under any circumstances, no matter how limited or irrespective of the reason? Congress could act to make out of print works universally available under terms similar to the Authors Guild’s proposal in the Google Book Search settlement, but so what? The mere fact that Congress could in theory set out a system that is broader than the limited scope for orphan works display that would be viable as fair use does not mean that there is no fair use.

Whatever it turns out to be, there is no basis to think that the university defendants’ orphan works project is a substitute for orphan works legislation.

Library Digitization v. Library Photocopying

If you proceed from the assumption that all unauthorized uses of a book are piracy then it makes sense that every new technology is just a new version of the photocopier. The Authors Guild Appeal Brief certainly can certainly be read as adopting the latter view.

The brief argues that “[t]he mechanical conversion of printed books into digital form is not transformative because it does not add any ‘new information, new aesthetics, [or] new insights and understandings,’ to the books.” (citing Pierre Leval, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105, 1111 (1990).) True, there is solid authority that photocopying and cable retransmission are not per se transformative (i.e., without looking at the reasons), but to suggest that library digitization offers no new insights is unsustainable.

Library digitization raises several different issues depending on the purpose behind that digitization and the uses that are subsequently made of the digitized texts. Library digitization could be motivated by any or all of the following:

- to preserve existing volumes

- to facilitate text-mining, data analysis and digital searching of the contents of books

- to facilitate access to electronic versions of books

The legal issues relating to each of these genres must be considered separately, but the Authors Guild’s brief muddles them altogether. Digitization does look a bit like other forms of copying if the motivating purpose is access or display of expressive works (i.e., #3 above). However, the argument in favor of a limited, non-commercial and education focused orphan works project turns not on transformative use, but on other considerations such as the lack of market harm [See Jennifer M. Urban, How Fair Use Can Help Solve the Orphan Works Problem (June 18, 2012)].

Likewise, the argument in favor of library digitization to facilitate disabled access is much broader than the details of the underlying technology. Whether we use the label transformative or not, this is clearly a favored purpose under the first fair use factor. The provision of equal access to copyrighted information for print-disabled individuals is mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The HathiTrust provides print-disabled individuals with access to millions of items within library collections, whereas in the past they merely had access to a few thousand at best. “Making a copy of a copyrighted work for the convenience of a blind person is expressly identified by the House Committee Report as an example of a fair use, with no suggestion that anything more than a purpose to entertain or to inform need motivate the copying.” (Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc, 464 U.S. 417, 455 n.40 (1984)).

The claim that library digitization is just like photocopying and does not offer any new insights crumbles completely when one considers the non-expressive uses such digitization makes possible. Library digitization makes it possible to extract meta-data from books and to create a useful search engine. Search indexing, text-mining and other computational uses of text could not be more different from mere photocopying; the “new information” and “new aesthetics” they offer include:

- Text-based searching

- Research on the structure of language

- Research on the use of language.

The database as a whole serves a different purpose than each of the constituent works that have been scanned and indexed. The individual works provide content to readers, they convey the authors original expression. The database as a whole provides a means of searching for and identifying books or analyzing the language within books.

Labels like transformative use and nonexpressive use can be helpful in grouping like cases together, but they can also be distracting. The issue of fair use is directly tied to a purposive reading of the Copyright Act and the purpose of copyright is clearly articulated in the U.S. Constitution—“[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts. . . .” As the Supreme Court stated in Campbell, the “central purpose” of the fair use investigation is to see, “whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message…”

The plaintiffs argue that library digitization is utterly untransformative, but in fact, digitization enabling book search and text-mining clearly leads to “new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings.”

For example, as we explained in the Digital Humanities Amicus Brief:

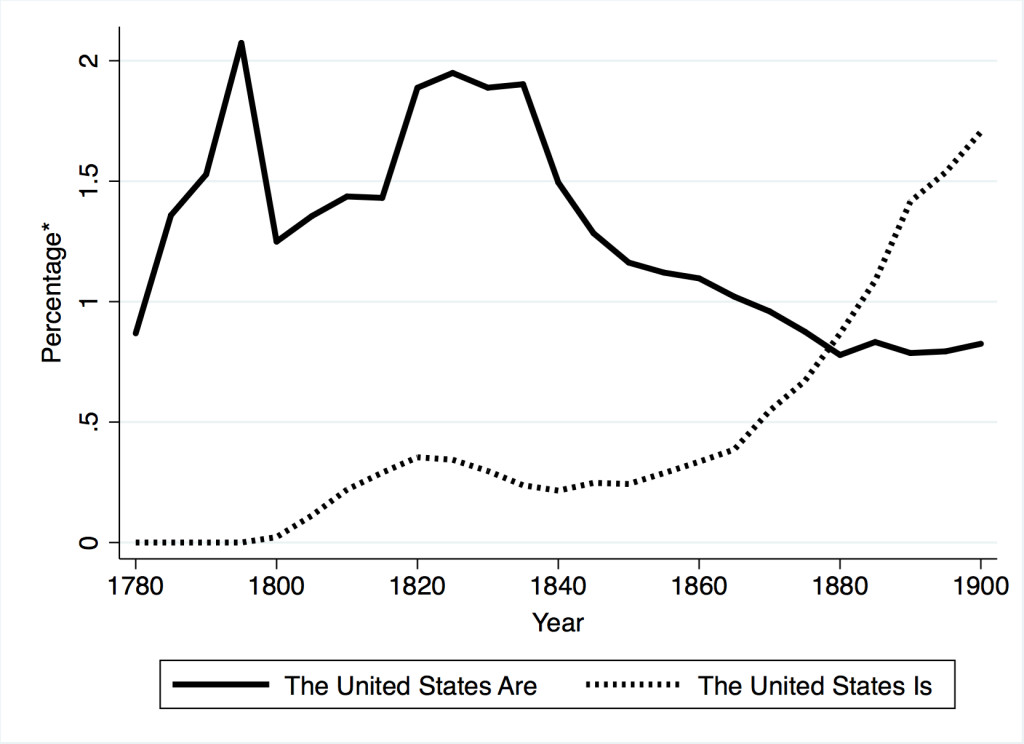

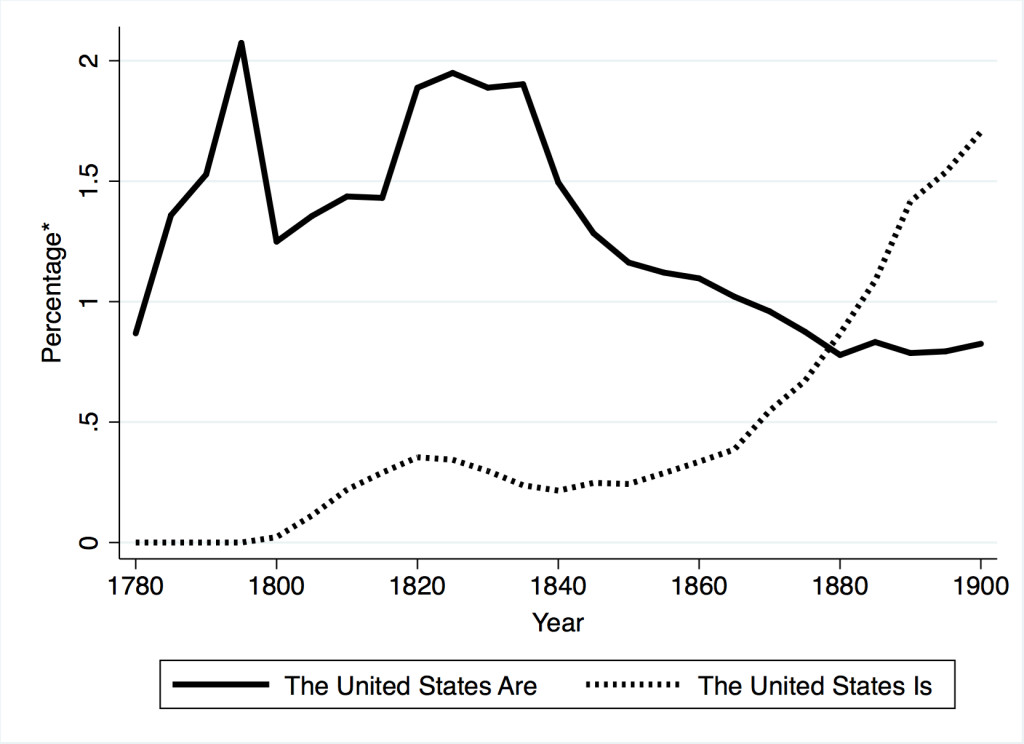

“Google’s “Ngram” tool provides another example of a nonexpressive use enabled by mass digitization—this time easily visualized. Figure 1, below, is an Ngram-generated chart that compares the frequency with which authors of texts in the Google Book Search database refer to the United States as a single entity (“is”) as opposed to a collection of individual states (“are”).

As the chart illustrates, it was only in the latter half of the Nineteenth Century that the conception of the United States as a single, indivisible entity was reflected in the way a majority of writers referred to the nation. This is a trend with obvious political and historical significance, of interest to a wide range of scholars and even to the public at large. But this type of comparison is meaningful only to the extent that it uses as raw data a digitized archive of significant size and scope. To be absolutely clear, 1) the data used to produce this visualization can only be collected by digitizing the entire contents of the relevant books, and 2) not a single sentence of the underlying books has been reproduced in the finished product. In other words, this type of nonexpressive use only adds to our collective knowledge and understanding, without in any way replacing, damaging the value of, or interfering with the market for, the original works.”

Library digitization is not the same as library photocopying.