I have just posted a new paper titled, Empirical Studies of Copyright Litigation: Nature of Suit Coding (http://ssrn.com/abstract=2330256). The paper investigates reliance on the Nature of Suit coding in the PACER records for empirical studies of copyright litigation. It concludes that although the PACER Nature of Suit for copyright does not in fact capture all copyright cases, it is a good enough sample for most purposes.

In spite of the increasing popularity of empirical legal studies more generally, there are relatively few empirical studies of copyright law, and even fewer of copyright litigation. This state of affairs cannot continue. The creation and distribution of copyrighted works is an important economic driver of the U.S. economy and copyright law’s interactions with freedom of expression and cultural participation have made it an area of significant public policy focus. If we truly want to understand copyright litigation we need to examine then we need to look at LITIGATION and not just at cases. But before we go too far down the rabbit hole of docket analysis, someone needs to ask whether we are studying the right dockets.

As part of a broader ongoing study of copyright litigation I selected every case in the Lexis database published (by lexis, not necessarily designated as such by the court) between 2000 and 2012 that included the word “copyright”. The search was designed to be over-inclusive. From this broad sample, I randomly selected one fifth of the district court opinions and all of the court of appeals opinions.

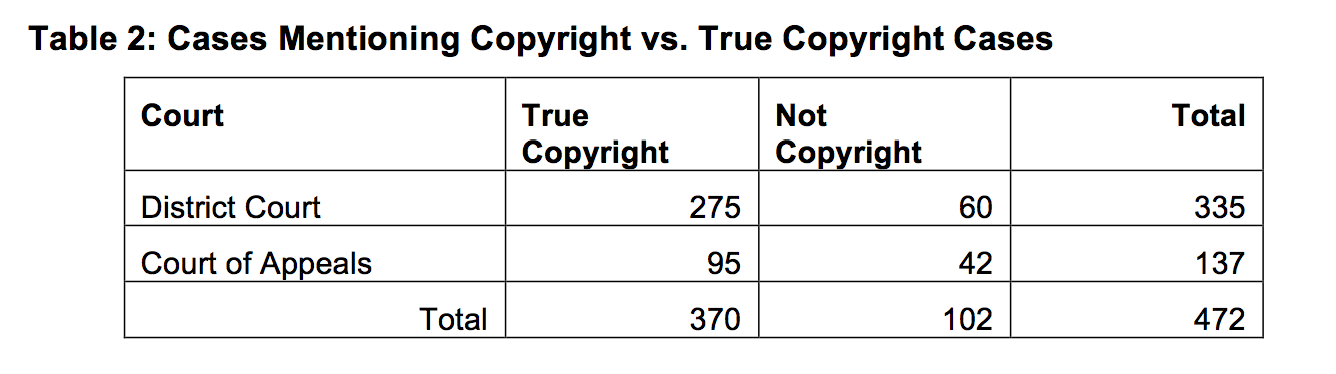

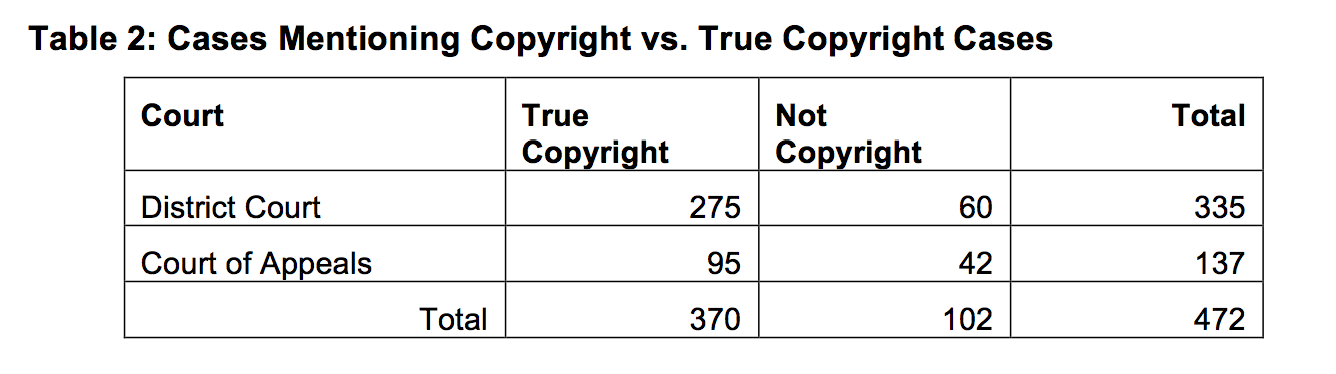

A team of Loyola Law School students reviewed each opinion following a detailed coding form and determined, among other things, whether the case was truly a copyright case. Of the 472 cases coded, 102 were not copyright cases. More specifically, of the 137 court of appeals cases and 275 district court cases selected, 42 appeals cases and 60 district court cases only mentioned copyright in passing or in the course of discussing copyright case law but did not relate to a claim of copyright infringement.

Determining the NOS coding for these true copyright cases was a simple, but laborious matter of cross-referencing the docket number with the PACER records. As set forth in Table 3, below, the almost 80% of district court cases and 85% court of appeals true copyright cases were filed as NOS=Copyright [820].

The “other” category included: Contract, Cable/Sat TV, Other Statutory Actions, Insurance, Assault, Libel, & Slander, Other Personal Property Damage, Civil Rights, Fraud, Personal Injury and even some criminal filings. What is does this imply for empirical research? Most obviously, it implies that docket analysis of copyright disputes relying solely on the nature of suit coding misses one in five of the kind of copyright case that is likely to end up as a written opinion at the district court level.

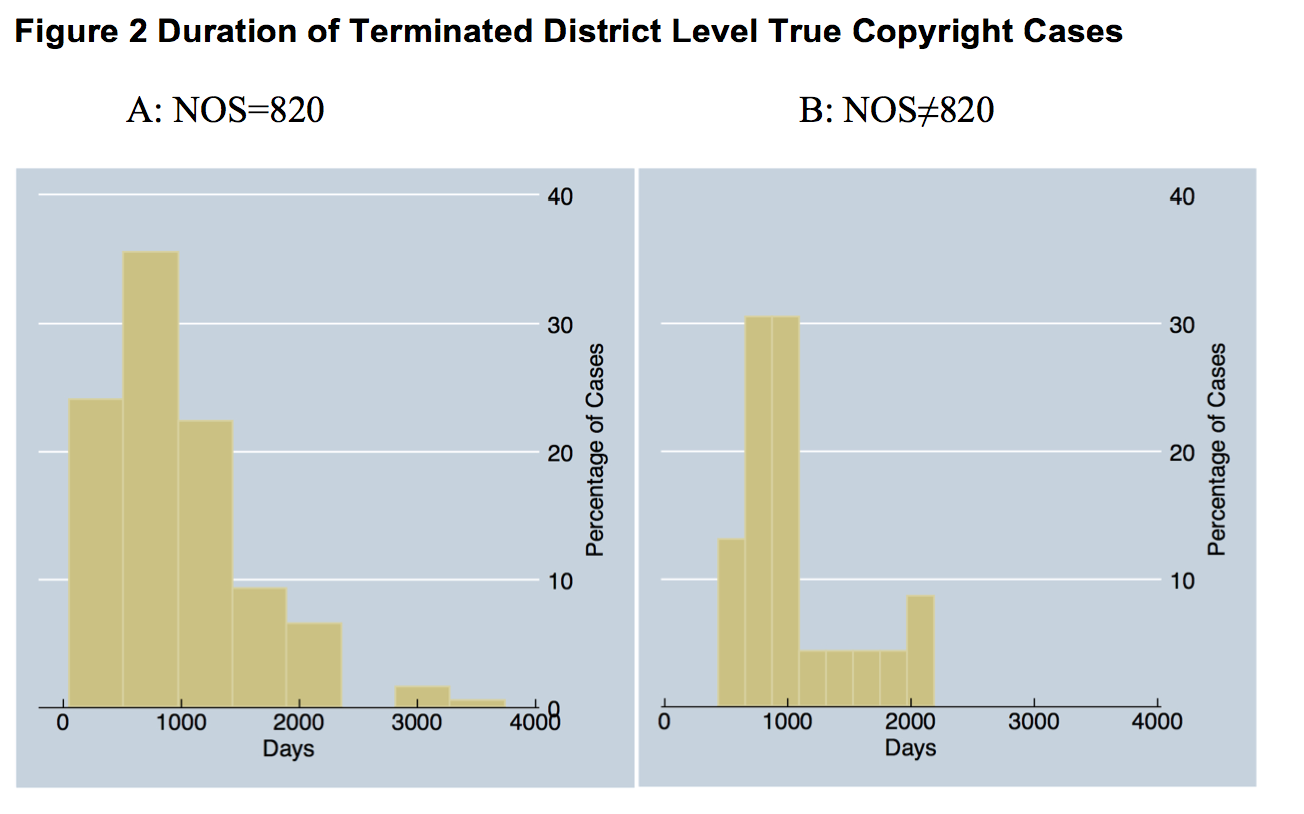

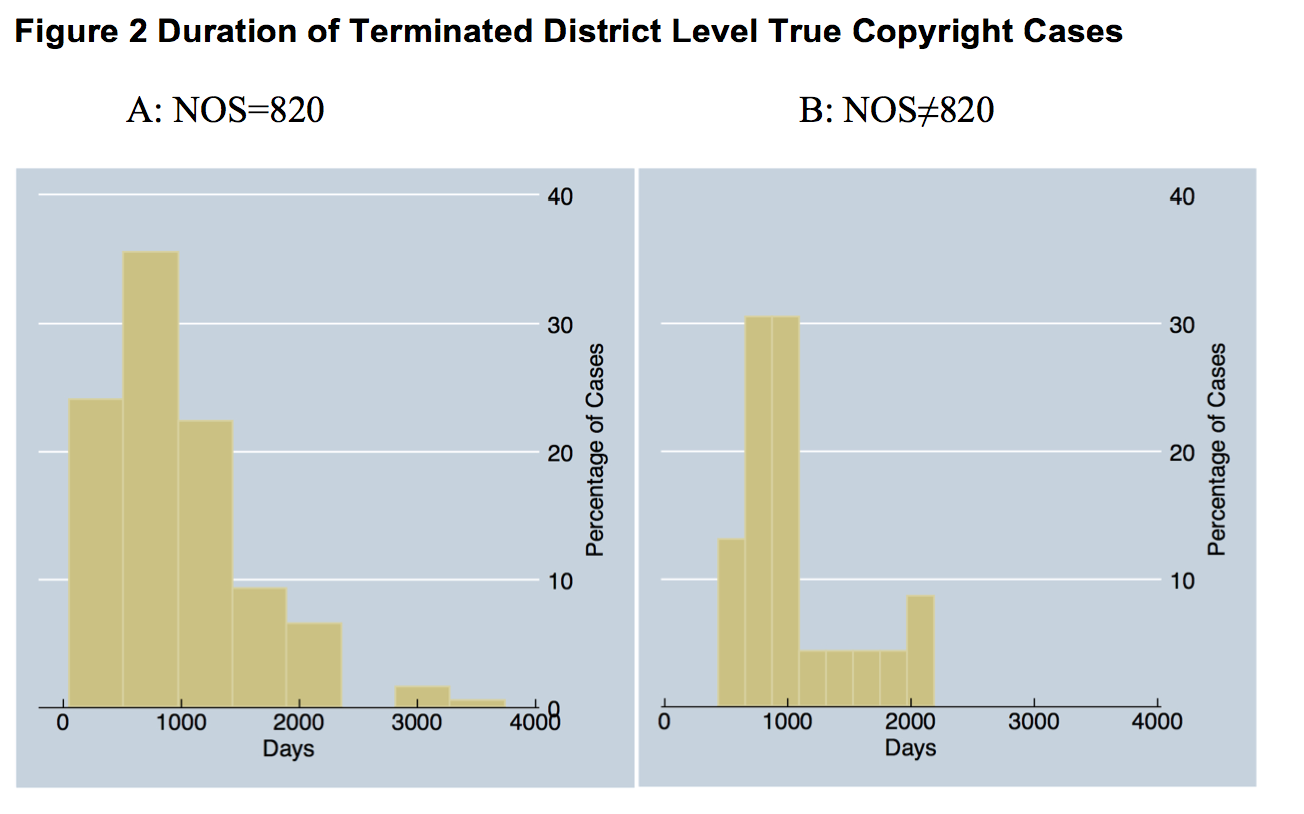

Is 80% good enough? It’s not bad. If we assume that most attorneys are competent enough to know what the major focus of their case is, then the copyright cases that are overlooked by focusing solely on the 820 cohort are likely to be only partially about copyright. However, researchers should also be aware that some dockets that grow up to be copyright cases, even some that make it into text books, will be missed by reliance on the 820 coding. They should this understand that selection is probably not random and may not be inconsequential. Consider, for example the difference in duration between district level true copyright cases coded as NOS=820 and those that were not.

The average duration of terminated district court true copyright cases was 752 days (488 median) if the case was filed as NOS=820. For the corresponding set filed as something other than NOS=820, the average duration was 506 days (479 median). The average duration of unterminated district court true copyright cases as of January 1, 2013 was 1232 days (1074 median) if the case was filed as NOS=820. For the corresponding set filed as something other than NOS=820, the average duration was 1099 days (942 median). Figures 1 and 2, below, present the same information in the form of histograms indicating the distribution of duration for all four categories.

In simple terms, district court true copyright cases tended to be longer in average duration if filed as NOS=820, although it is noteworthy that they are not that different at the median.

What does all this mean for empirical studies of copyright litigation?

My conclusion is that, for copyright, at least, although the PACER Nature of Suit for copyright does not in fact capture all copyright cases, as long as researchers are clear about their methods and what data they are excluding, it is a good enough enough sample for most purposes.