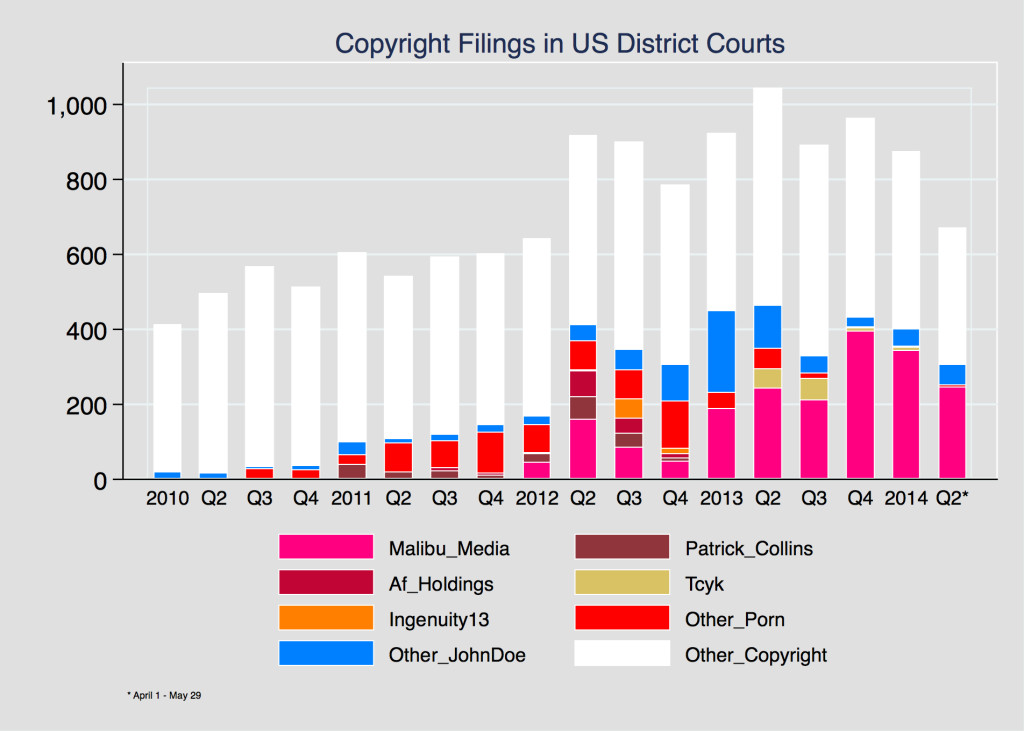

I will be presenting my research on Copyright Trolling (download the full paper from ssrn) at the Law And Society Annual Meeting today. This morning I updated my data to May 29, 2014 and created this figure to show the incredible influence of Malibu Media and a handful of other prolific pornography plaintiffs. The data is divided by quarter from Q1 2010 to the present.

Updated Copyright Trolling and Pornography Data for 2014

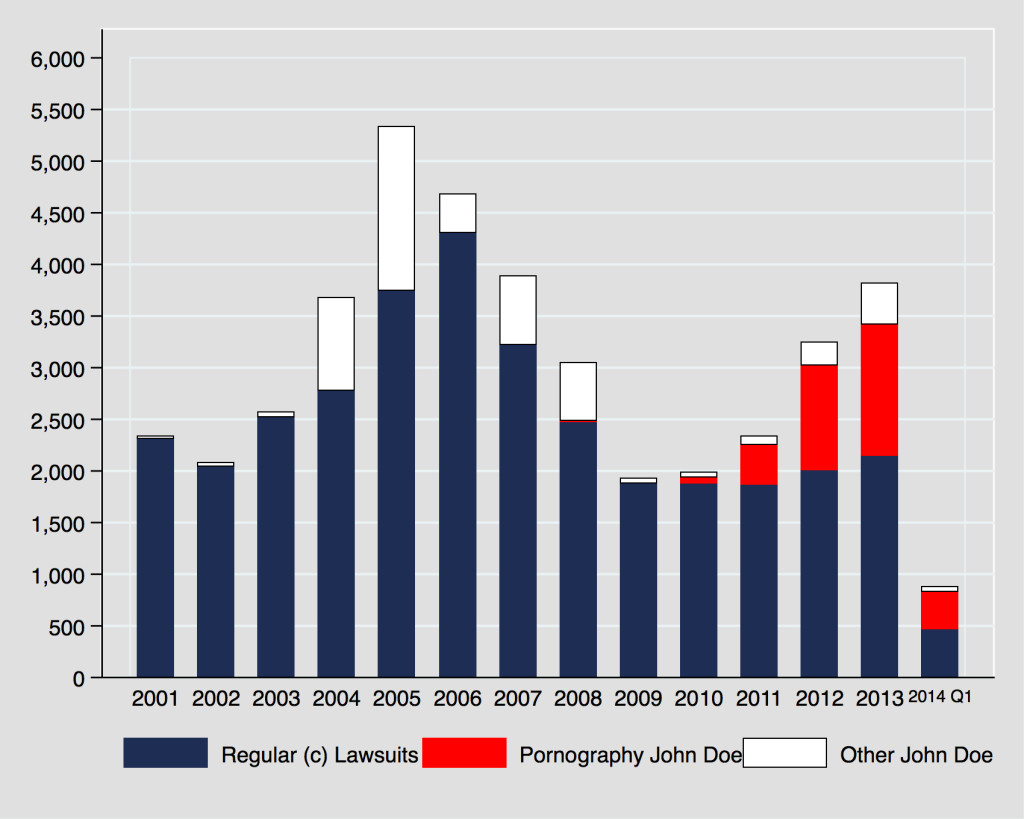

Copyright Lawsuits Filed in U.S. Federal Courts 2001 – 2014

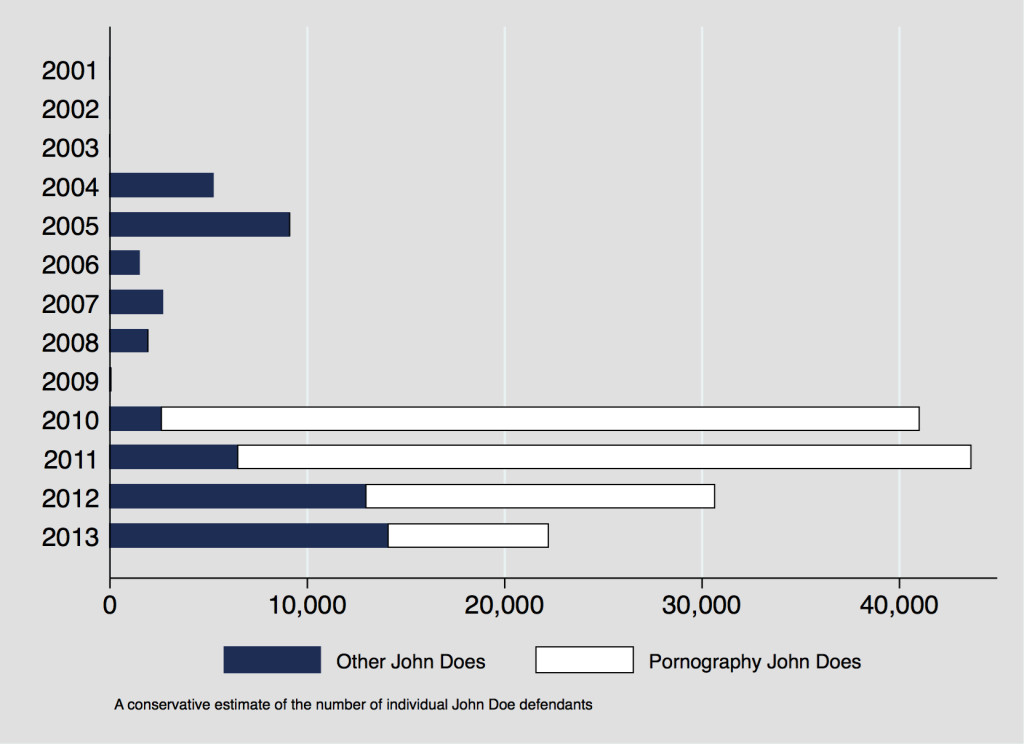

This graphs is from my forthcoming article, Copyright Trolling, An Empirical Study. The graph illustrates the effect of two separate waves of John Doe litigation. The first wave was the recording industry’s battle with filesharing technology from 2004 through 2008. The second wave began in 2010 and continues through to the present and is dominated to a remarkable degree by lawsuits relating to pornography.

There is an article in the New Yorker Online today about this phenomenon with a a closeup view of one the major plaintiffs, Malibu Media, see THE BIGGEST FILER OF COPYRIGHT LAWSUITS? THIS EROTICA WEB SITE, BY GABE FRIEDMAN . Well worth a read.

Patent troll statistics, a correction

In a post on Friday I mentioned that in 2012, businesses and individuals targeted by patent aggregators and patent holding companies accounted for fifty-six percent of all patent defendants. That number should actually be 37.8% of all patent defendants.

There are estimates of even higher numbers, see Colleen Chien, Patent Trolls by the Numbers reporting RPX’s estimate that PAEs initiated 62% of all patent litigation suits in 2012. However, it is not exactly clear how RPX determines who is and is not a patent troll. Also RPX is in the business of providing “patent risk management services”, so it is not exactly a disinterested bystander in the patent troll debate.

Christopher A. Cotropia, Jay P. Kesan & David L. Schwartz, Unpacking Patent Assertion Entities (PAEs) have provided some great data on this issue – but it still needs to be read carefully to understand what it means.

Figure 3 of that paper reports patent litigation numbers in terms of the number of individual defendants sued.

On this metric:

- suits by large aggregators and patent holding companies increased from 31.6% of all patent litigation in 2010 to 37.8% in 2012;

- in contrast suits by operating companies went down from 48.9% in 2010 to 47.3% in 2012;

- if you include the IP holding companies of operating companies, suits by operating companies went down from 51.0% in 2010 to 47.8% in 2012;

Cotropia, Kesan & Schwartz round out this picture by reporting the numbers for universities & colleges, individuals & family trusts, failed operating companies & failed start-ups, and technology development companies. Some of these suits may be troll litigation, but without case specific information it is hard to tell.

Some measured thoughts on patent trolls

This post expands on the remarks I made today at the Chicago Tech Roundtable meeting on Patent Trolls and Chicago’s Tech Community. The meeting was attended by a number of elected officials and their representatives as well as start-ups such as Jump Rope and Options Away Travel who have had direct experiences with patent trolls. This is an important issue for Chicago’s technology sector.

Trolls and Trolling – The Nature of the Problem

Patent trolls are in the news and they have been high on the agenda of intellectual property policy makers and academics for over a decade now. I started thinking about these issues when I worked as an IP lawyer in Silicon Valley in the early 2000’s. The Federal Trade Commission sounded an important call to action on patent trolls and the balance of competition and patent law and policy in 2003 [FTC, To Promote Innovation: The Proper Balance of Competition and Patent Law and Policy, (2003)], and again in 2011 [FTC, The Evolving IP Marketplace: Aligning Patent Notice and Remedies with Competition (2011)].

I first wrote about these issues in a paper published in 2007, Patent Reform and Differential Impact (with Kurt W. Rohde who was then a student of mine and is now is a partner with McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP), some things have changed since then, but the patent trolls problem persists, it may even be getting worse. In 2012, businesses and individuals targeted by patent aggregators and patent holding companies accounted for 58 37.8% of all patent defendants.

* An earlier version of this post contained the assertion that businesses and individuals targeted by patent aggregators and patent holding companies accounted for 58% of all patent defendants. That was a very unfortunate transcription error.

Not every non-practicing entity, patent aggregator and patent holding company is a necessarily a troll. There is obviously a role in our innovation ecosystem for people who invent but don’t have the complementary skills to commercialize. But the rough and ready correlation between patent assertion entities and trolls seems to fit. Any business that is sending out infringement notices by the hundreds or thousands can’t plausibly be doing the kind of diligence it should take to make a meritorious claim of infringement.

Debating who is and is not a troll is beside the point – it is trolling behavior that we need to address. Trolling is abusive and opportunistic behavior such as asserting bad patents or using patents to extort settlements that are only justified by the threat of legal fees. Trolling is mostly a numbers game – trolls targets hundreds or thousands of defendants, seeking quick settlements priced just low enough that it is easier for the defendant to pay the troll directly rather than pay his lawyers to defend the claim. Anyone who takes part in this kind of systematic opportunism that undermines innovation is a troll, NPE or not.

Patent trolls thrive by opportunistically taking advantage of the uncertain scope of patent claims, the poor quality of patent examination, the high cost of litigation and the asymmetry of risks and costs of litigation. There is nothing wrong with licensing your technology, or with litigating against infringers who would rather take your technology without a license. The patent system is meant to encourage investment in R&D and innovation. Businesses monetizing their technology aught to be celebrated, but using the threat of costly litigation to monetize bad or ill-fitting patent claims takes money away from R&D budgets for no social gain.

Solutions

There will always be opportunists who try to exploit the system – the goal of patent reform should be to limit unproductive rent-seeking while leaving the door open to those businesses that actually contribute to the research and development that makes the U.S. a world leader in so many fields. We need reforms targeted at bad patents such as limiting continuations, rejecting highly abstract functional claims (especially in software and business method patents) and improving the quality of patent examination. But we also need reforms targeted at bad conduct. We need reforms that level the litigation playing field — it is far too easy to impose millions of dollars of defense costs based on dubious patents and tenuous theories of the scope of those patents. Some of the most useful reforms— reforms that leave the door open for well-founded claims — include: fee shifting such that the losing party pays the winning party’s fees in ordinary cases; heightened pleading standards; delaying discovery until after “claim construction,” and limiting discovery to those documents likely to be relevant to the specific litigation at hand. “Consumer stay” provisions would also do a lot to end opportunistic threats of litigation – under this proposal if, for example, a cafe was sued by offering Wi-Future interest to its customers, the manufacturer of the router could intervene and effectively consolidate the cases of all of its customers. Reforms aimed at transparency of patent ownership and taking action against misleading and deceptive language in demand letters would also be of some assistance.

House recently passed the Innovation Act to take up some of these issues and the Senate Judiciary Committee seems close to finalizing a complementary bill. Neither of these bills will put an end to opportunism, but they have the potential to make life a harder for patent trolls and a little easier for the rest of us.

Patent Troll Statistics

According to RPX Corporation PAEs initiated 62% of all patent litigation suits in 2012. [See Colleen Chien, Patent Trolls by the Numbers (http://patentlyo.com/patent/2013/03/chien-patent-trolls.html)] However, it is not exactly clear how RPX determines who is and is not a patent troll. Also RPX is in the business of providing “patent risk management services”, so it is not exactly a disinterested bystander in the patent troll debate.

The best empirical analysis of patent troll numbers so far is contained by Christopher A. Cotropia, Jay P. Kesan & David L. Schwartz, Unpacking Patent Assertion Entities (PAEs) (working paper available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2346381). Figure 3 of that paper reports these numbers in terms of the number of individual defendants sued. On this metric:

- suits by large aggregators and patent holding companies increased from 31.6% of all patent litigation in 2010 to 37.8% in 2012;

- in contrast suits by operating companies went down from 48.9% in 2010 to 47.3% in 2012;

- if you include the IP holding companies of operating companies, suits by operating companies went down from 51.0% in 2010 to 47.8% in 2012;

Cotropia, Kesan & Schwartz round out this picture by reporting the numbers for universities & colleges, individuals & family trusts, failed operating companies & failed start-ups, and technology development companies. Some of these suits may be troll litigation, but without case specific information it is hard to tell.

Garcia v. Google amicus briefs with very brief summaries

Due to the level of interest in Garcia v. Google, the Ninth Circuit has a dedicated page providing information and key court documents to the public.

I have listed the Amicus briefs along with very cursory descriptions below. The briefs are all quite short.

Internet Law Professors — addressing the implications of the Court’s decision for Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Section 230 is vital to the health of e-commerce and web 2.0 businesses, it provides the legal foundation for many of the most popular websites that enable users to communicate with each other or the world at large. The panel’s broad interpretation of copyright law undermines Section 230 immunity without even expressly considering it. * I am one of the Amici for this brief.

Professors of Intellectual Property Law — arguing that the Court’s opinion misinterprets the baseline requirements for copyrightability. ** This is the brief to read for students of copyright law.

Adobe Systems, et al. It is not surprising that eBay, Facebook, Gawker, Kickstarter, Pinterest, Tumblr, Twitter, and Yahoo! would feel strongly about this case. These amici argue that the Court’s decision and order places too much responsibility on service providers to monitor their services and denies the public’s interest in free expression and access to information. They also argue that the Court’s order is unworkable and that the ruling poses a serious threat to online service providers’ businesses.

Netflix, Inc. — arguing that that the ruling creates a new species of copyright and risks wreaking havoc with established copyright and business rules on which third party distributors, such as Netflix, depend.

International Documentary Ass’n — arguing that the Court’s opinion has created uncertainty as to several fundamental concepts that are essential to modern filmmaking.

Floor64 (publisher of Techdirt.com) & Organization for Transformative Works —arguing that the Court’s decision undermines Congress’s goal of fostering online speech by effectively stripping intermediaries of the statutory protection they depend on to deliver it — i.e. the safe harbors created by the § 230 of the Communications Decency Act and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (17 U.S.C. § 512).)

California Broadcasters — arguing that a finding that individual performances within films and television programs may be entitled to copyright protection creates uncertainly for entertainment media creators and distributors.

News Organizations — arguing that the Court’s decision did not properly consider important First Amendment interests and that it poses serious risk to news organizations that extend far beyond the unique facts of the case at hand.

Electronic Frontier Foundation, et al. — framing the issues in Constitutional terms and addressing the standard for preliminary injunctions.

Public Citizen Litigation Group — focusing on the correct standard for issuing an injunction restraining speech.

ABC v. Aereo Supreme Court Law Professor Amicus Brief

This amicus brief was written by David Post and James Grimmelmann on behalf of 36 law professors in the pending case of ABC v Aereo, now before the Supreme Court (oral argument set for April 22, 2014).

Testing my rss feeds

Let me know if this post came up in your rss feed.

New Jersey’s anti-Tesla laws and the car dealership racket

Over 70 economists and law professors have signed a letter opposing New Jersey’s direct automobile distribution ban.

Why should you care?

This ban is aimed at keeping the Tesla electric car out of New Jersey, but this effects you even if you have no interest in an electric car. State laws protecting car dealerships add thousands of dollars to the cost of every new car. NPR’s Planet Money program has an excellent summary of this issue.

The International Center for Law & Economics sent an open letter to New Jersey Governor Chris Christie today, urging reconsideration of the regulation.

As the letter notes:

… the regulations in question are motivated by economic protectionism that favors dealers at the expense of consumers and innovative technologies. It is discouraging to see this ban being used to block a company that is bringing dynamic and environmentally friendly products to market.

Among the letter’s signatories are some of the country’s most prominent legal scholars and economists from across the political spectrum.

Read the letter here: Open Letter to New Jersey Governor Chris Christie on the Direct Automobile Distribution Ban

Read Geoffrey Manne‘s post on Truth On The Market

New Copyright Troll Data

I have revised my paper Copyright Trolling, An Empirical Study (March 21, 2014) (forthcoming in the Iowa Law Review) (http://ssrn.com/abstract=2404950) to include data for all US district courts from 2001 to 2013.

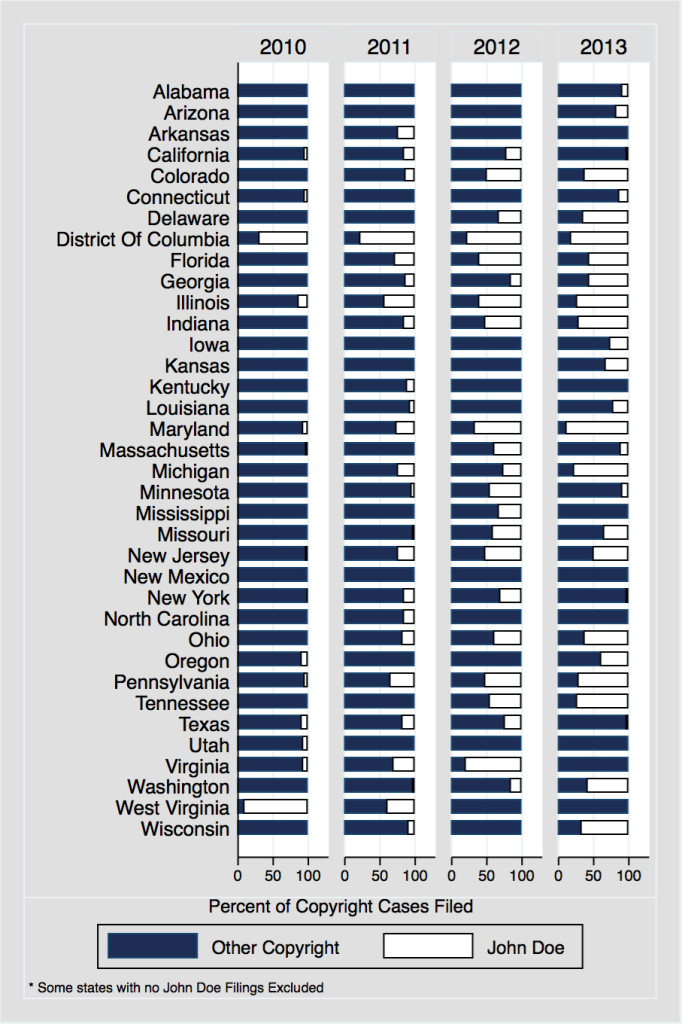

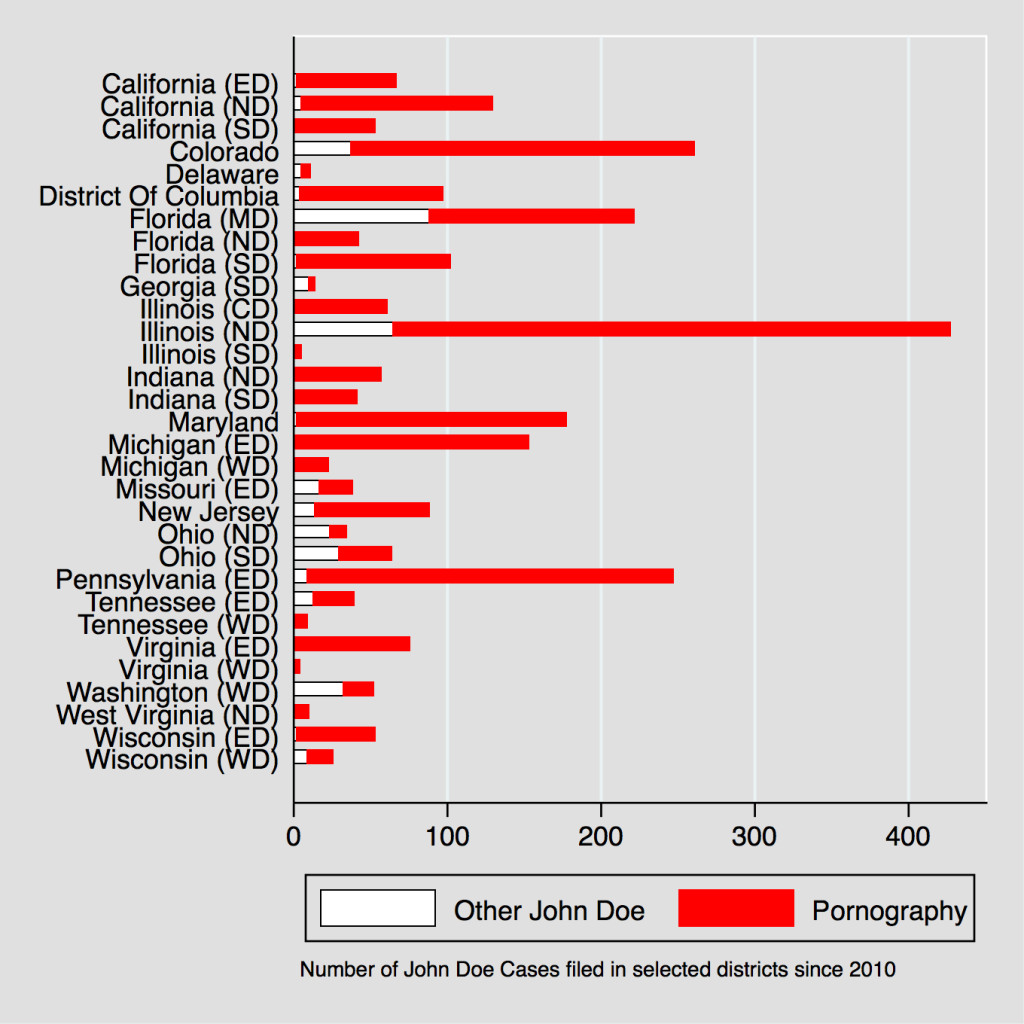

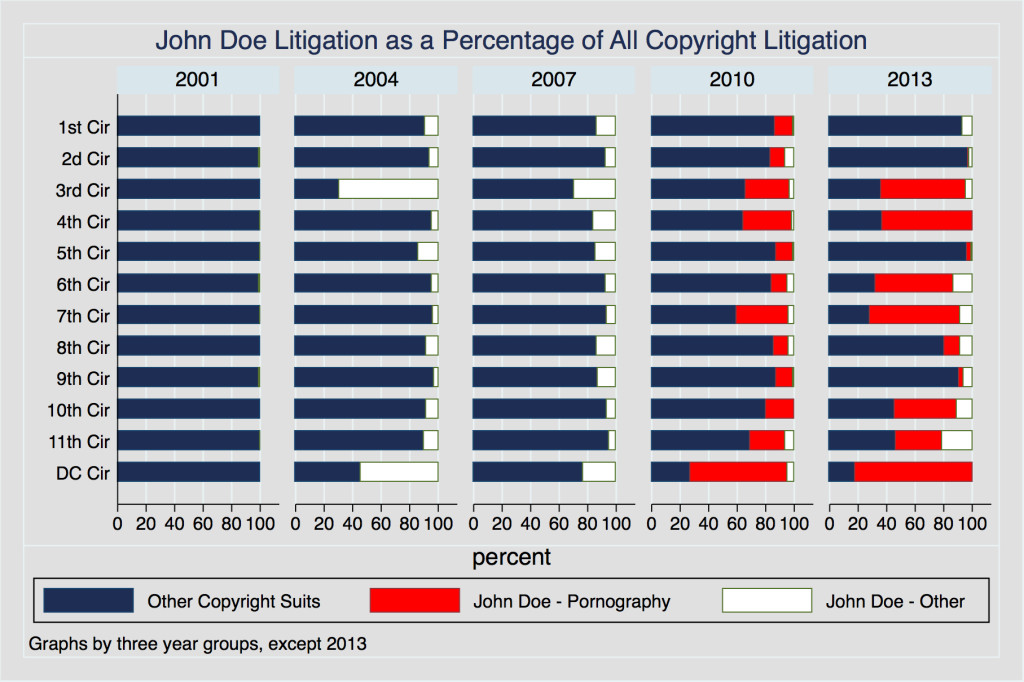

The following are a few of the new figures from the paper. The new data is discussed in the article.

John Doe lawsuits as a percentage of all copyright lawsuits 2010–2013, by State

John Doe Copyright Lawsuits 2010–2013 Selected Districts

Individual Doe Defendants in John Doe Copyright Cases 2001 – 2013

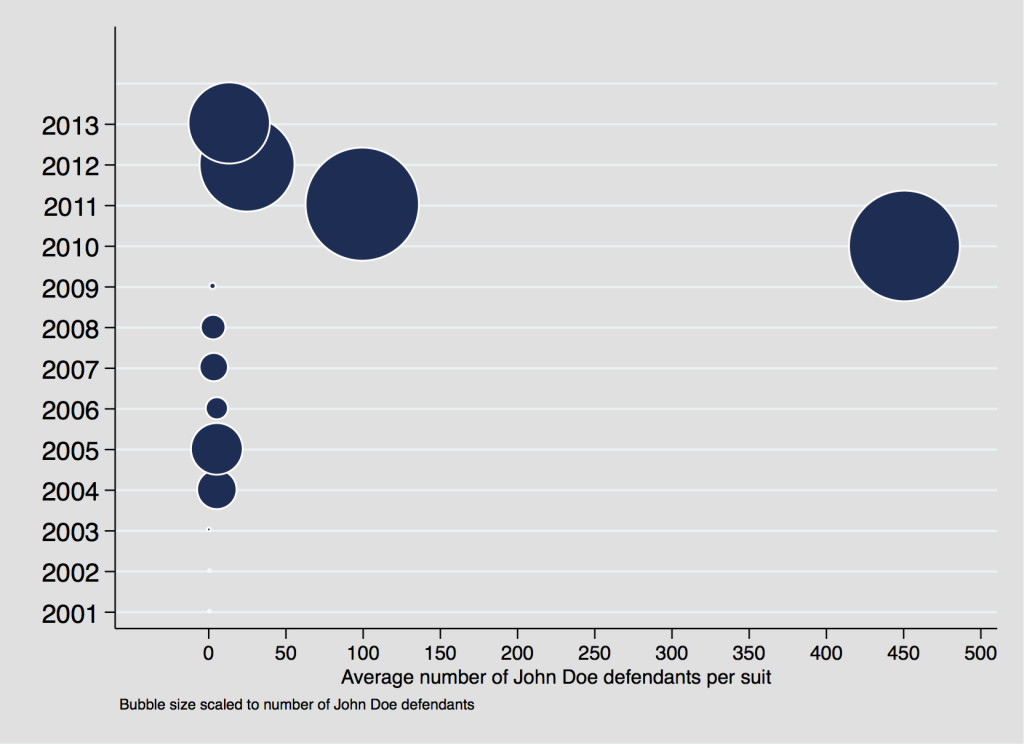

Average Number of Doe Defendants per Suit 2001 – 2013

A graph of John Doe suits as a percentage of all copyright cases filed

For more details see Copyright Trolling, An Empirical Study (this is still the version posted last week, a new version with additional data will be out soon).