I posted a guest-blog over at the Authors Alliance explaining why digital humanities researchers support google’s fair use defense in Authors Guild v. Google. The Authors Alliance supports Google’s fair use defense because it helps authors reach readers. In my post, I explained another reason why this case is important to the advancement of knowledge and scholarship.

Earlier this month a group of more than 150 researchers, scholars and educators with an interest in the ‘Digital Humanities’ joined an amicus brief urging the Second Circuit Court of Appeals to side with Google in this dispute. Why would so many teachers and academics from fields ranging from Computer Science, English Literature, History, Law, to Linguistics care about this lawsuit? It’s not because they are worried about Google—Google surely has the resources to look after itself—but because they are concerned about the future of academic inquiry in a world of ‘big data’ and ubiquitous copyright.

For decades now, physicists, biologists and economists have used massive quantities of data to explore the world around them. With increases in computing power, advances in computational linguistics and natural language processing, and the mass digitization of texts, researchers in the humanities can apply these techniques to the study of history, literature, language and so much more.

Conventional literary scholars, for example, rely on the close reading of selected canonical works. Researchers in the ‘Digital Humanities’ are able to enrich that tradition with a broader analysis of patterns emergent in thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of texts. Digital Humanities scholars fervently believe that text mining and the computational analysis of text are vital to the progress of human knowledge in the current Information Age. Digitization enhances our ability to process, mine, and ultimately better understand individual texts, the connections between texts, and the evolution of literature and language.

A Simple Example of the Power of the Digital Humanities

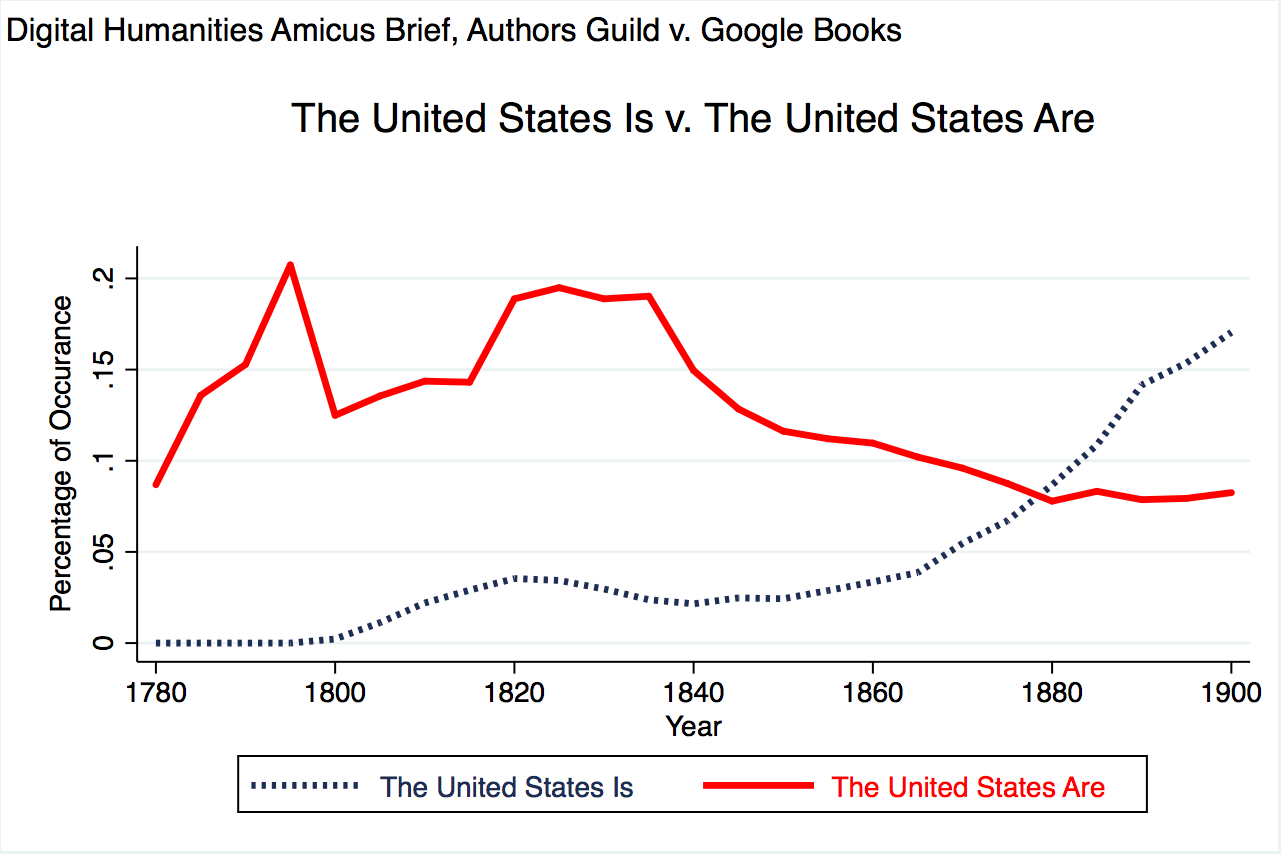

The figure below, is an Ngram-generated chart that compares the frequency with which authors of texts in the Google Book Search database refer to the United States as a single entity (“is”) as opposed to a collection of individual states (“are”). As the chart illustrates, it was only in the latter half of the Nineteenth Century that the conception of the United States as a single, indivisible entity was reflected in the way a majority of writers referred to the nation. This is a trend with obvious political and historical significance, of interest to a wide range of scholars and even to the public at large. But this type of comparison is meaningful only to the extent that it uses as raw data a digitized archive of significant size and scope.

There are two very important things to note here. First, the data used to produce this visualization can only be collected by digitizing the entire contents of the relevant books–no one knows in advance which books to look in for this kind of search. Second, not a single sentence of the underlying books has been reproduced in the finished product. The original authors expression was an input to the process, but it was not a recognizable part of the output. This is the fundamental distinction that the Digital Humanities Amici are asking the court to preserve–the distinction between ideas and expression.

Will Copyright Law Prevent the Computational Analysis of Text?

The computational analysis of text has opened the door to new fields of inquiry in the humanities–it allows researchers to ask questions that were simply inconceivable in the analog era. However, the lawsuit by the Authors Guild threatens to slam that door shut.

For over 300 years Copyright has balanced the author’s right to control the copying of her expression with the public’s freedom to access the facts and ideas contained within that expression. Authors get the chance to sell their books to the public, but they don’t get to say how those books are read, how people react to them, whether they choose to praise them or pan them, how they talk to their friends about them. Copyright protects the author’s expression (for a limited time and subject to a number of exceptions and limitations not relevant here) but it leaves the information within that expression and information about that expression “free as the air to common use.” The protection of expression and the freedom of non-expression are both fundamental pillars of American Copyright law. However, the Author Guild’s long running campaign against library digitization threatens to erase that distinction in the digital age and fundamentally alter the balance of copyright law.

In the pre-digital era, the only reason to copy a book was to read it, or at least preserve the option of reading it. But this is no longer true. There are a host of modern technologies that literally copy text as an input into some larger data-processing application that has nothing to do with reading. For want of a better term, we call these ‘non-expressive uses’ because they don’t necessarily involve any human being reading the authors original expression at the end of the day.

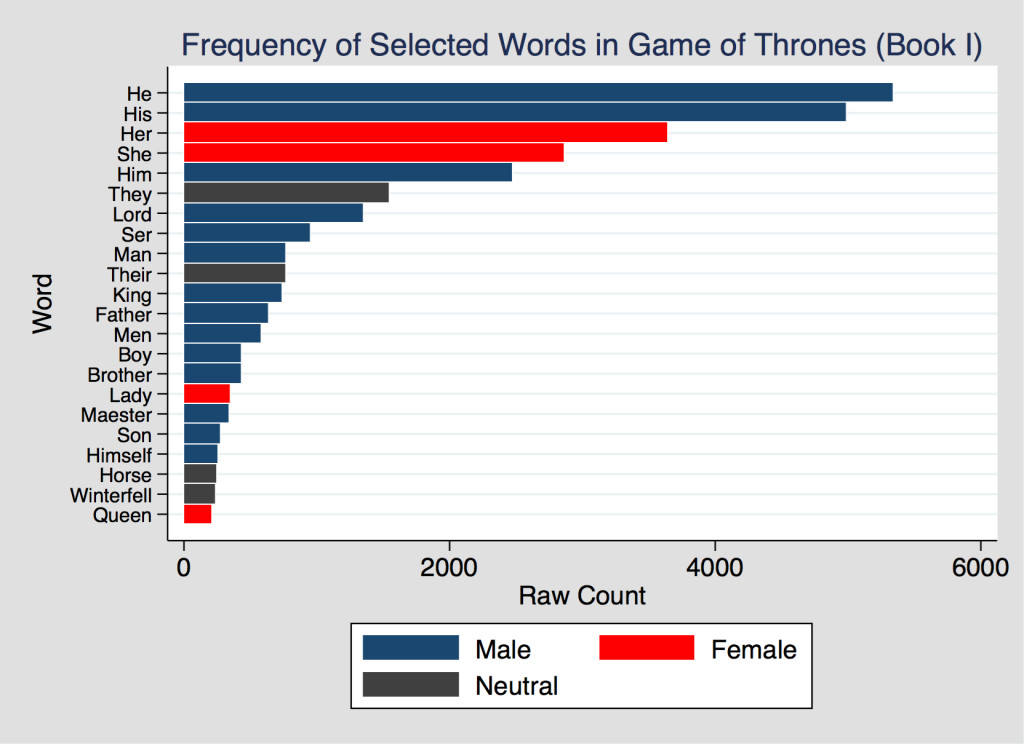

Most authors, if asked, support making their works searchable because they want them to be discovered by new generations of readers. But this is not our central point. Our point is that if it is permissible for a human to pick up a book and count the number of occurrences of the word “whale” (1119 times in Moby Dick) or the ratio of male to female pronouns (about 2:1 in A Game of Thrones Book 1—A Song of Ice and Fire), etc., then there is no reason the law should prevent researchers doing this on a larger and more systematic basis.

Digitizing a library collection to make it searchable or to allow researchers to analyze create and analyze metadata does not interfere with the interests that copyright owners have in the underlying expression in their books.

Who knows what the next generation of humanities researchers will uncover about literature, language, and history if we let them?

You can download the Brief of Digital Humanities and Law Scholars as Amici Curiae here.