On March 29, 2017, I attended a fantastic conference on “Globalizing Fair Use: Exploring the Diffusion of General, Open and Flexible Exceptions in Copyright Law” hosted by American University Washington College of Law’s Program and Information Justice and Intellectual Property. As part of that event we held a webcast Q&A session moderated by Sasha Moss of the R Street Institute. The following is rough transcript of my comments in response to Sasha’s questions about the legality of the non-expressive use copyrighted works.

Copyright Questions For the Digital Age

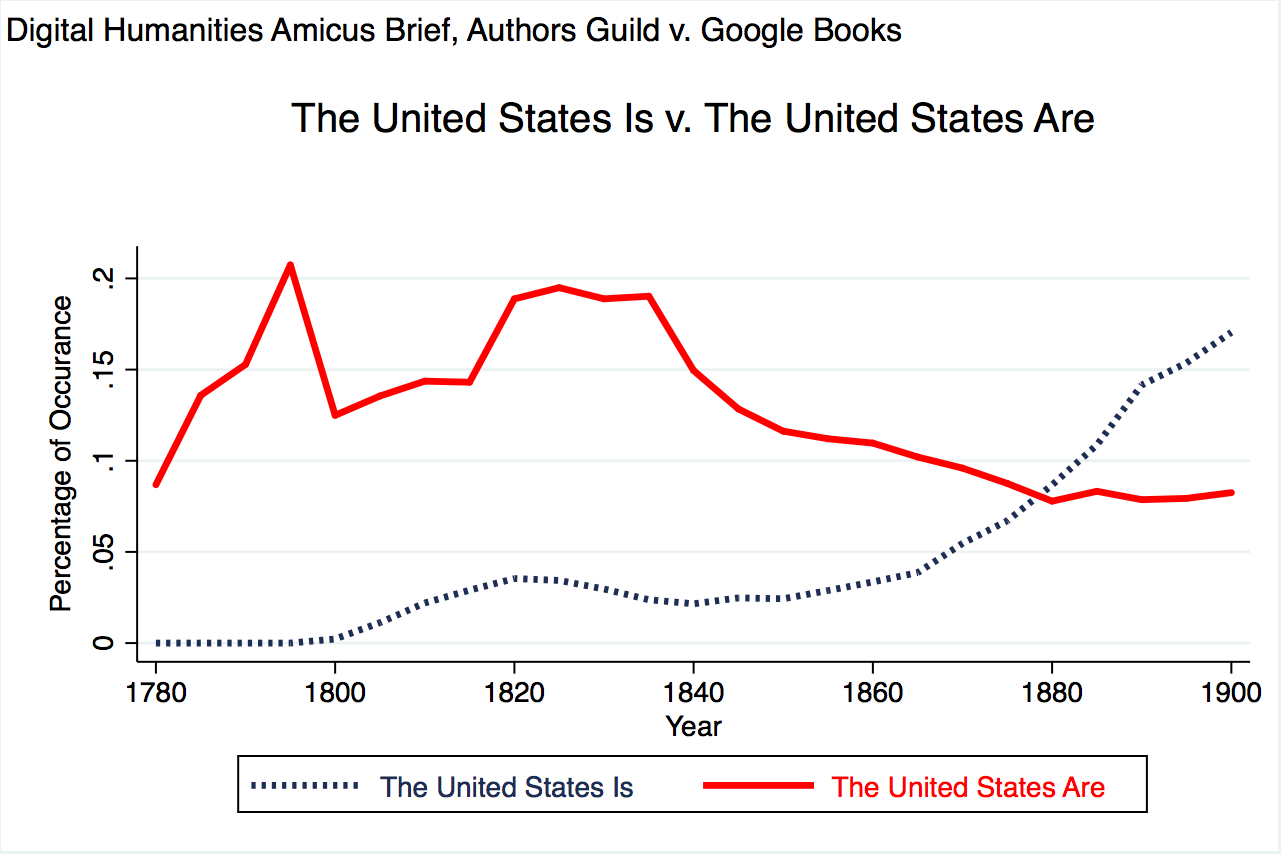

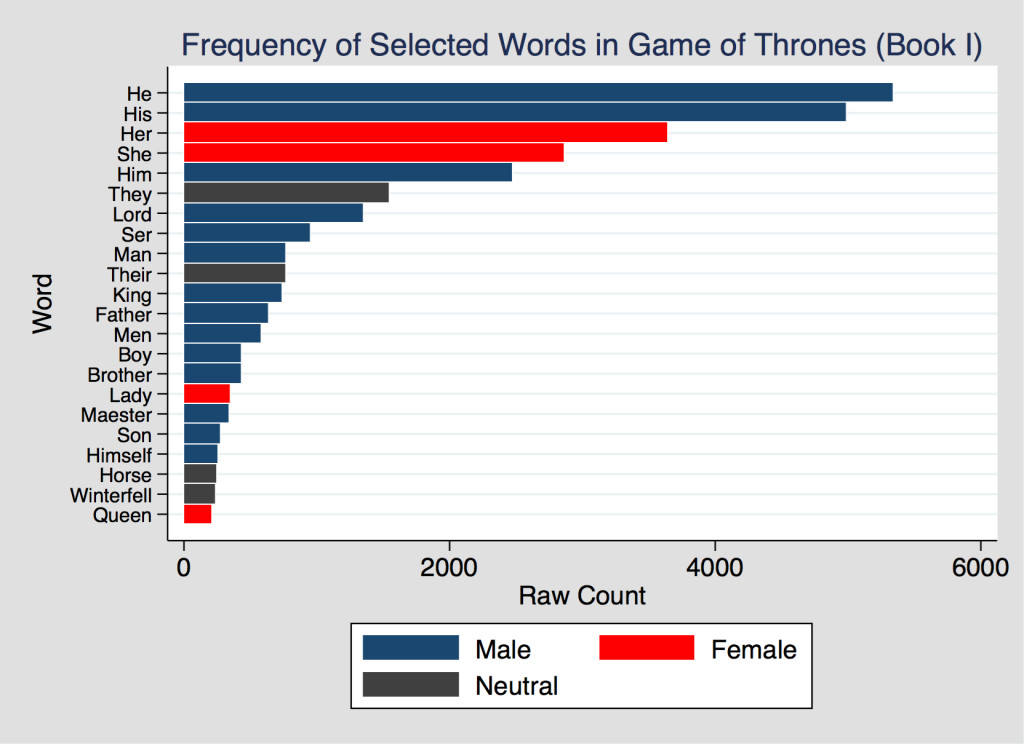

There is no country in the world where simply reading a book and giving someone information about the book, such its subject or themes, whether it uses particular words or particular combinations of words, the number of words, the number of pages, the ratio of female to male pronouns, etc., would amount to copyright infringement.

Why? Because information about the book is not the book. It is metadata. The question for the digital age is, “Can we use computers to produce that kind of data?” This question is important because although I can read a few books and produce some useful metadata, I can’t read a million books. But a computer can.

We have the technology

We have the technology to digitize large collections of books in order to produce data that enables computer scientists, linguists, historians, English professors, and the like, to answer important research questions. The data and the questions it can be used to answer do nothing to communicate the original expression of all those millions of books. However, technically speaking, this kind of digitalization is still copying.

But is this the kind of copying that copyright law should be concerned about? If a tree falls in an empty forest, does it truly make a sound? If something is copied but only read by a computer and the computer only communicates metadata about the work, is that the kind of copying this should amount to copyright infringement?

Text mining is vital for machine learning, automatic translation, and developing the language models

It seems to me, that once you phrase the question that way the answer is clear. We all use this amazing technology on a daily basis when we rely on Internet search engines, but text mining use is about much more than this. By data mining vast quantities of scientific papers, researchers have been able to identify new treatments for diseases. Text mining has also allowed humanities scholars to identify patterns in vast libraries of literature. Text mining is vital for machine learning, automatic translation, and developing the language models the power dictation software.

Fair use and technological advantage

The United States is a world leader in various applications of text mining, starting with Internet search, but going far beyond that. In the United States, once people realized what was possible they more or less start doing it. If Larry Page and Sergy Brin had had the idea for the Google Internet search engine in Canada, Australia, England, or Germany in the 1990s it would have been crystal-clear that because their search engine relied on making copies of other people’s HTML webpages and there was no realistic way to obtain permission from all those people, building search engine would be illegal. In countries with a closed list of copyright exceptions and limitations, or with fair dealing provisions that are tied to specific narrowly defined purposes, a lawyer would have looked at the list and said, “I don’t see Internet search or data mining on that list, so you can’t do it.”

The fair use doctrine reinforces copyright rather than negating it

In the United States, we have the fair use doctrine, which means that the list is not closed. In the United States, the fair use doctrine means you at least get a chance to explain why your particular use of a copyrighted work is for a purpose that promotes the goals of copyright, is reasonable in light of that purpose, and is unlikely to harm the interests of copyright owners. The fair use doctrine reinforces copyright rather than negating it; fair use doesn’t mean that you get to do whatever you want. Fair use is a system for determining how copyright should apply in new situations. That is especially important whether the law was written decades ago and society and technology are changing fast.

Without something like fair use, other countries can only follow the United States

Without something like fair use, other countries can only follow the United States. Non-expressive uses of copyrighted works such as text mining, building an Internet search engine, or running plagiarism detection software have all been held to be fair use in the United States and are slowly becoming more accepted around the world. Of course, now that it is readily apparent that these activities are immensely beneficial and entirely non-prejudicial to the interests of copyright owners we could probably write some specific amendments to the copyright act to make them legal. The problem is, do we didn’t know this two decades ago when we actually needed those rules. I don’t know what the next thing that we don’t know is, but I do know that experience has shown that the flexibility of the fair use doctrine—which has been part of copyright law virtually since the English Statute of Anne in 1710, by the way—has worked better than a system of closed lists.

The fair use doctrine is a real source of competitive advantage for technologists and academic researchers in the United States. Right now, there are technologies being developed and research being done in the United States that either can’t be done in other countries, or can only be done by particular people subject to various arbitrary restrictions. Whether it’s Internet search, digital humanities research, machine learning or cloud computing, other countries have followed the United States in adopting technologies that make non-expressive use of copyrighted works, because some of the copyright risks begin to look less daunting once the practice has become accepted. The Europeans, for example, are pretty sure building a search engine must be legal, but they can’t quite agree why. But the thing to understand is that you can follow this way but you can never lead. It’s much harder to do the new thing if by the letter of the law it is illegal and you have no forum to argue that it should be allowed.

The future doesn’t have a lobby group

Of course, that’s not quite true, you have one forum … you can spend a vast amount of money are lobbyists and go to the government, go to Congress and try to get some favorable rules written. But even if that is successful from time to time, those rules have a particular character. A company that spends millions of dollars on a lobbying campaign to change the law is always going to try and make sure that those new rules only benefit its business. Special interests will get some laws changed, but usually in ways that disadvantage their competitors or exclude alternative technologies that might one day compete with them. The fundamental problem with relying on static lists of copyright exceptions and lobbying to get those lists revised as needed is that the future doesn’t have a lobby group.

If you would like to read more about these topics:

- Matthew Jockers, Matthew Sag & Jason Schultz, Brief of Digital Humanities and Law Scholars in Support of Defendants-Appellees and Affirmance in Authors Guild v. Google (13-4829) (July 10, 2014)

- Matthew Jockers, Matthew Sag & Jason Schultz, Digital Archives: Don’t Let Copyright Block Data Mining, 490 Nature 29-30 (October 4, 2012)

- Matthew Sag, Orphan Works as Grist for the Data Mill, 27 Berkeley Technology Law Journal 1503 – 1550 (2012)

- Matthew Sag, Copyright and Copy-Reliant Technology, 103 Northwestern University Law Review 1607–1682 (2009)