Introduction and Necessary Disclaimer

This one of a series of posts concerning the Authors Guild v. Hathitrust case, specifically these posts take the form of commentary on the Authors Guild Appeal Brief (February 25, 2013). Although I am one of the authors of the Digital Humanities and Law Scholars Amicus Brief, the views expressed on this site are purely my own. My comments on the Authors Guild’s Appeal Brief will not be comprehensive, rather, my aim is to review the aspects of the brief that I found interesting.

Today’s topic …

What is the Authors Guild really saying about orphan works?

In some ways, the Authors Guild is the victim of its own success. The Authors Guild was quick to discover some defects in the way that the University of Michigan was determining orphan works status when the project was first announced in 2011. Exposure of those issues led to the suspension of that project before any single work was distributed to the public as an orphan work. The orphan works project might come back in some form at some stage, but at the moment there is no way for the court to know what kind of orphan works project it was being asked to rule on or who it would effect.

In its appeal brief, the Guild responds to this predicament by arguing that the orphan works part of its case is ripe for adjudication because the details simply don’t matter – any orphan works project would be unlawful! See e.g.

“Any iteration of the OWP under which copyrighted works are made available for public view and download violates the Copyright Act. The pure legal question that was presented to the District Court is the same as it will always be: Is it ever lawful to take an entire copyright-protected book and make it widely available for display and download without permission?” (Authors Guild Ap. Br. page 13; see generally pages 13-14).

And later

“Plainly, existing copyright law does not permit the copying and distribution of the entirety of copyright-protected works to tens of thousands of users, irrespective of whether it might be difficult to locate the rights-holder.” (Authors Guild Ap. Br. page 17)

I don’t know how the defendants will respond to this argument and it is not an issue that fits within the scope of the Digital Humanities Amicus brief. Rather than diving into the legal arguments as to when and why the display of orphan works would be fair use, I thought it might be illuminating to consider an example.

Orphan works example: the Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website

On April 12, 2012, I attended the opening session of the Berkeley Law School’s “Orphan works and Mass Digitization” conference. The topic of the first panel was “Who wants to make use of orphan works and why.” In the course of that panel, Bruce Hartford, the webmaster of the Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website told a story so fascinating it is worth setting in full.

The Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website recounts the history of the civil rights movement:

“This website is created by Veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement (1951-1968). It is where we tell it like it was, the way we lived it, the way we saw it, the way we still see it. With a few minor exceptions, everything on this site was written, created, or spoken by Movement activists who were direct participants in the events they chronicle.” (http://www.crmvet.org)

Much of the material on the Civil Rights Movement Veterans website is used with permission or requires no permission because it is in the public domain. However, according to Hartford, that still leaves a significant proportion of material that he would classify as orphan works. When Hartford uses the term orphan works he means (i) material that was originally copyrighted by an organization which no longer exists and made no provision for its copyrights upon dissolution; (ii) material where the copyright owner cannot be found; (iii) or material where the identity of the copyright owner was always unknown.

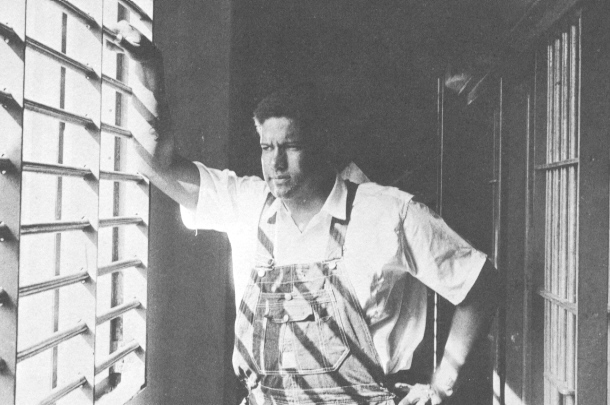

The photo below of James Forman (October 4, 1928 – January 10, 2005), an American Civil Rights leader active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

As Hartford described it:

“The camera was smuggled into the jail, given to an unknown prisoner who clicked the button and took the picture. Under copyright law, as I am told, the copyright to the picture is owned by the unknown prisoner who pressed the button on the camera, who then gave it back to whoever smuggled the camera into the prison, to smuggle it out of the prison.

Now I know this is off topic, but I am just going to say, some of us are a little annoyed about this stupid rule that the person who presses the button totally owns the rights and those of us who are risking our lives to do whatever it was that they were taking the picture of have no say so in whatever happens to that and they can make lots of money on it and we can look and weep.”

Take another look

Take another look at the photo of James Forman, consider what it means to the Civil Rights Movement Veterans Website and ask yourself, can it really be true, as the Authors Guild state in their brief, that “[p]lainly, existing copyright law does not permit the copying and distribution of the entirety of copyright-protected works to tens of thousands of users, irrespective of whether it might be difficult to locate the rights-holder.” (Authors Guild Ap. Br. page 17)?