On March 14, 2025, I submitted my comments to the Office of Science and Technology Policy in relation to the “AI Action Plan”. For context, the Office of Science and Technology Policy requested input on the Development of an Artificial Intelligence (AI) Action Plan to define the priority policy actions needed to sustain and enhance America’s AI dominance, and to ensure that unnecessarily burdensome requirements do not hamper private sector AI innovation. See Exec. Order No. 14,179, 90 Fed. Reg. 8741 (Jan. 31, 2025)(Executive Order titled “Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence,” signed by President Trump).

What follows is a lightly edited version of those comments (mostly removing footnotes, but also making a couple minor improvements).

AI Action Plan, Submission to the Office of Science and Technology Policy

I am the Jonas Robitscher Professor of Law in Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Data Science, Emory University. I appreciate the opportunity to contribute to OSTP’s call for policy ideas aimed at enhancing America’s global leadership in Artificial Intelligence (AI).

My primary points in this submission are that if, contrary to precedent and sound policy, American courts rule that training AI models on copyrighted works is not permissible as fair use, the U.S. government must be ready to act. And furthermore, to maintain U.S. leadership in artificial intelligence, the AI Action Plan should explicitly affirm the importance of broad copyright exceptions—particularly fair use for nonexpressive activities like AI model training.

How copyright law in various countries deals with AI training

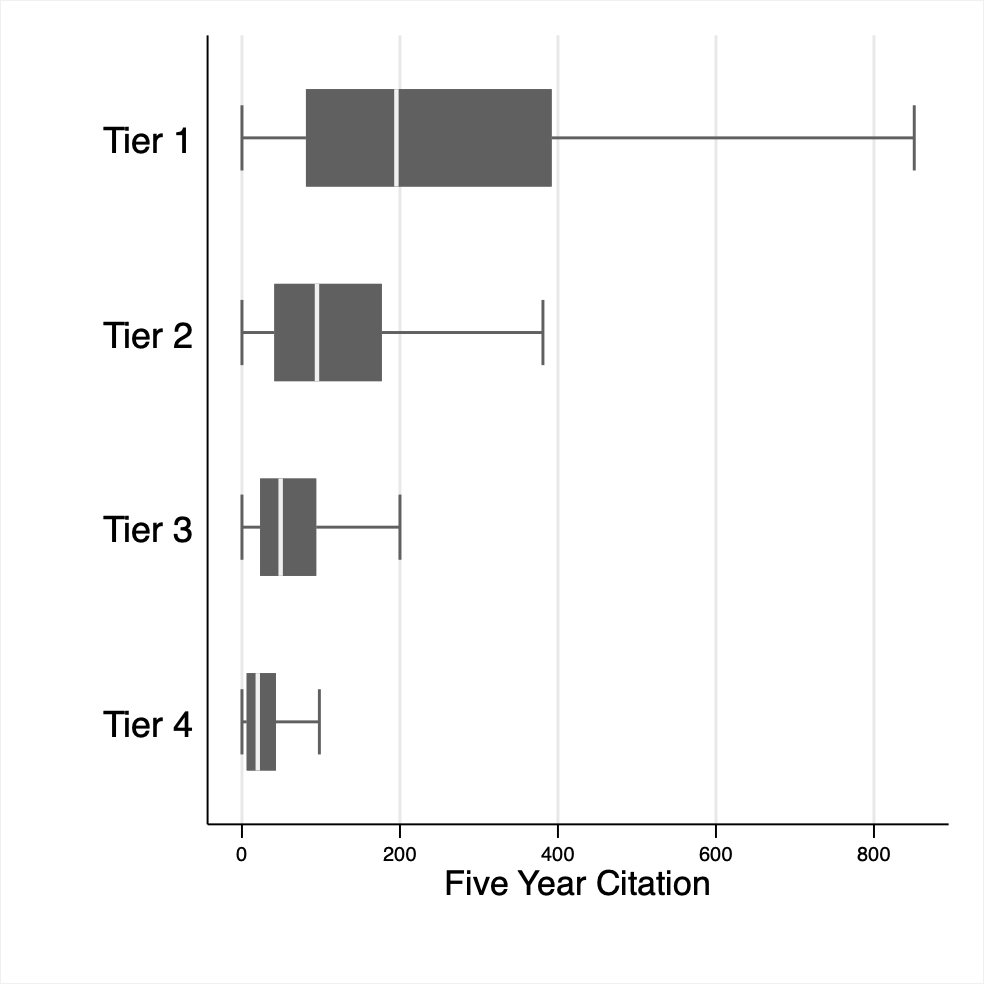

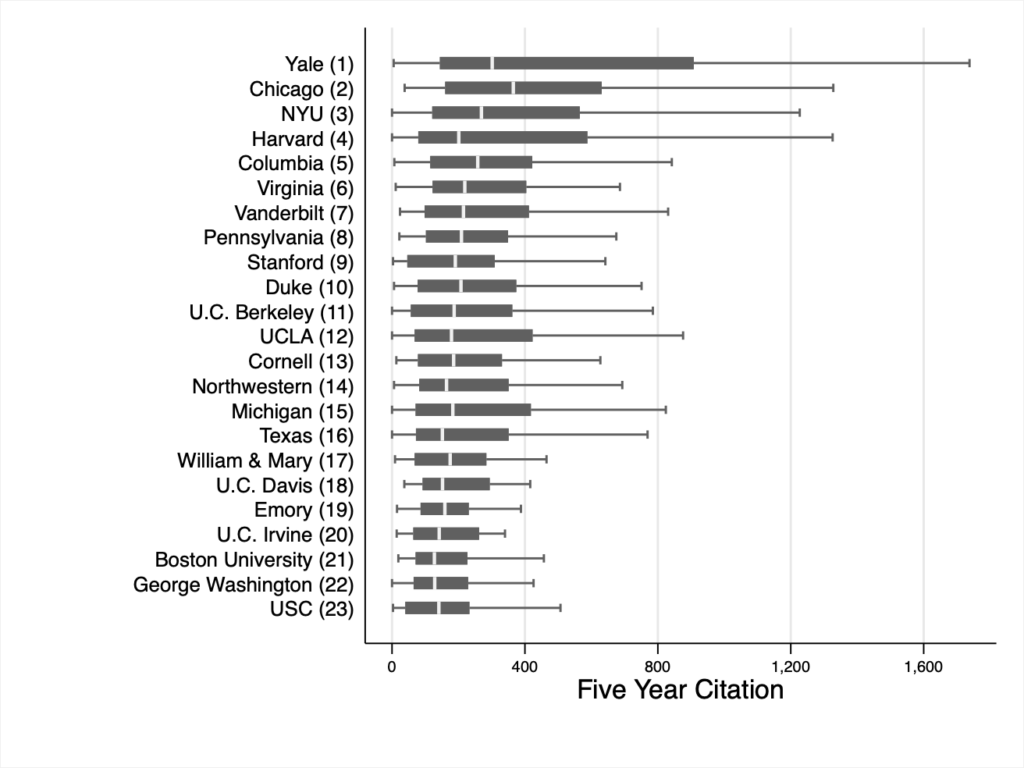

In “The Globalization of Copyright Exceptions for AI Training” my co-author Professor Peter Yu and I examine how copyright frameworks across the world have addressed the apparent tension between copyright law and copy-reliant technologies such as computational data analysis in the form of text data mining (TDM), machine learning and AI.

Our research reveals that, although the world has yet to achieve a true consensus on copyright and AI training, an international equilibrium has emerged. In this equilibrium, countries recognize that TDM, machine learning and AI training can be socially valuable and do not inherently prejudice the copyright holders’ legitimate interests. Policymakers in the European Union, Japan, Israel, and Singapore agree in general terms that such uses should therefore be allowed without express authorization in some, but not necessarily all, circumstances.

Major industrialized economies have found different ways to this equilibrium position. Some, like the U.S. and Israel have done so through the fair use doctrine. Others, like Japan, Singapore, and the European Union, have crafted express copyright exceptions for TDM and computational data analysis. Other nations where the rule of law is not so clearly established are energetically pursuing AI development with state backing without updated copyright laws to facilitate AI training. There is little doubt that if the Chinese Communist Party deems copyright law an impediment to its AI ambitions, the law in China will change almost instantaneously, and very likely retrospectively.

U.S. litigation could unsettle global AI copyright norms

American courts have historically recognized fair use protections for technologies relying on nonexpressive copying, such as reverse engineering, plagiarism detection software, digital library searches, and computational humanities research spanning millions of scanned texts. Extending this principle logically, training AI models—which similarly involves copying without directly reproducing expressive content—would usually qualify as fair use. (For citations and discussion of the relevant literature, see Matthew Sag, Fairness and Fair Use in Generative AI, 92 Fordham Law Review 1887 (2024))

Yet, plaintiffs in more than 30 ongoing lawsuits across U.S. district courts contest this view. Collectively, they seek injunctions barring AI training without explicit consent, billions in monetary compensation, and even destruction of existing AI models. Although, in my estimation and that of many copyright experts, the plaintiffs are should not prevail on sweeping arguments that would bring AI training in the U.S. to a halt, they might.

A bad court decision may drive AI innovation offshore

Adverse outcomes in U.S. litigation will not stop the development of AI, they will simply push AI innovation overseas. The reason is straightforward: AI models, once trained, are easily portable. Companies seeking to avoid restrictive copyright rules could simply move their training operations to innovation-friendly jurisdictions like Singapore, Israel, or Japan, and then serve U.S. customers remotely, entirely free of domestic copyright concerns.

How is this possible? AI developers need fair use for all the copying that takes place to make training possible, but they don’t need fair use once the models have been trained because, by-and-large, trained AI models do not replicate the expressive details of their training datasets; instead, they distill general patterns, abstractions, and insights from that training data.

Thus, in the eyes of copyright law, these models are neither copies nor derivative works based on the training data. If U.S. copyright law turns against our AI industry, companies in the U.S. will still be able to use models trained in AI-friendly jurisdictions by either setting up a data pipeline so that the model stays overseas or hosting their models in the United States once it has been trained. Consequently, imposing overly restrictive copyright interpretations domestically will do very little to turn back the tide on AI, but risks surrendering America’s AI advantage to more AI-friendly jurisdictions.

Licensing deals are no substitute for fair use

While licensing agreements between AI developers and media companies are becoming more common, they cannot solve copyright concerns surrounding AI training. The sheer scale of AI training data makes the licensing approach impractical at the cutting edge. For instance, Meta’s recent Llama 3 model consumed over 15 trillion (15,000,000,000,000) tokens drawn from publicly accessible sources. To put this into perspective, assuming that the New York Times print edition is roughly fifty pages per day, each page has 4000 words (this is probably way over!), and there are 1.3 tokens per word, the newspaper would generate roughly 1.82 million tokens per week. At that rate, it would take about 158,500 years for the New York Times to generate 15 trillion tokens.

Licensing may be possible for some AI training, but licensing at the scale required to train frontier LLMs is not a realistic foundation for American industrial policy, it is a fantasy.

Nevertheless, existing deals with major media companies illustrate something important: AI developers are willing to pay for efficient access to high-quality datasets otherwise locked behind paywalls or machine-readable restrictions. Such agreements suggest that licensing has a niche but crucial role—not as a substitute for broad exceptions like fair use, but rather as a complementary source of premium training data. This dynamic becomes particularly valuable in AI-powered search scenarios, where language models frequently generate outputs closely resembling original copyrighted content, pushing the boundaries between acceptable use and potential infringement.

The U.S. Government must be ready to act

If, contrary to precedent and sound policy in my view, American courts rule that training AI models on copyrighted works is not permissible as fair use, the U.S. government should act. Specifically, the government would need to introduce legislation to reinstate the principle that training AI models typically falls under fair use or create a specific statutory exemption. I see no way this could be done through agency rulemaking or executive action. Legislative intervention would be necessary to safeguard America’s competitive edge against innovation-friendly jurisdictions like Japan, Singapore, Israel, and, in this context, even the European Union.

To maintain U.S. leadership in artificial intelligence, the AI Action Plan should explicitly affirm the importance of broad copyright exceptions—particularly fair use for nonexpressive activities like AI model training.