Some additional thoughts on the 7th Circuit’s decision in Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation LLC, No. 13-3004 (7th Cir. Sept. 15, 2014).

Judge Easterbrook expressed some skepticism today over the Second Circuit’s decision in Cariou v. Prince, 714 F. 3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013) because …

asking exclusively whether something is “transformative” not only replaces the list in §107 but also could override 17 U.S.C. §106(2), which protects derivative works. To say that a new use transforms the work is precisely to say that it is derivative and thus, one might suppose, protected under §106(2).

Easterbrook complains that

Cariou and its predecessors in the Second Circuit do not explain how every “transformative use” can be “fair use” without extinguishing the author’s rights under §106(2).”

Ok, so let me explain.

First, Cariou and its predecessors don’t say that every transformative use is fair use. Second, more importantly, transformative use and derivative work are both important terms of art in copyright law. They are not the same thing. Nobody thinks they are.

Section 106(2) of the Copyright Act gives copyright owners an exclusive right to prepare derivative works based on the copyright owner’s original work. As defined in the statute, a derivative work takes a preexisting work and “recasts, transforms, or adapts” that work. The kind of transformations referred to here are not necessarily ‘transformative’ as that term was intended by the Supreme Court in the context of fair use. And yes, obviously, using a word that is not a stem of ‘transform’ would have helped.

A transformative work, in the fair use sense, is one which imbues the original “with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” [Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 579 (1994) (internal citations omitted).] Thus, the assessment of transformativeness is not merely a question of the degree of difference between two works; rather it requires a judgment of the motivation and meaning of those differences.

The difference between a non-infringing transformative use and an infringing derivative work can be illustrated as follows: if Pride and Prejudice were still subject to copyright protection, the novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, which combines Austen’s original work with scenes involving zombies, cannibalism, and ninjas, would be considered a transformative parody of the original, and thus fair use rather than infringement. In contrast, a more traditional sequel would merely be an infringing derivative work.

The term transformative use has been applied to cases of literal transformation where it overlaps with the kinds of manipulations that might also create a derivative work. Thus in Suntrust Bank v. Houghton Mifflin Co, substantial copying of a novel in the service of criticism was regarded as transformative.

The term transformative use has been applied to cases of copying without modification, but for a good reason. For example in Savage v. Council on American-Islamic Relations, Inc., the Islamic organization copied and distributed anti-Islamic statements made by Michael Savage as part of a fund-raising exercise. Recontextualization without modification from one expressive context to another was seen as transformative Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd.

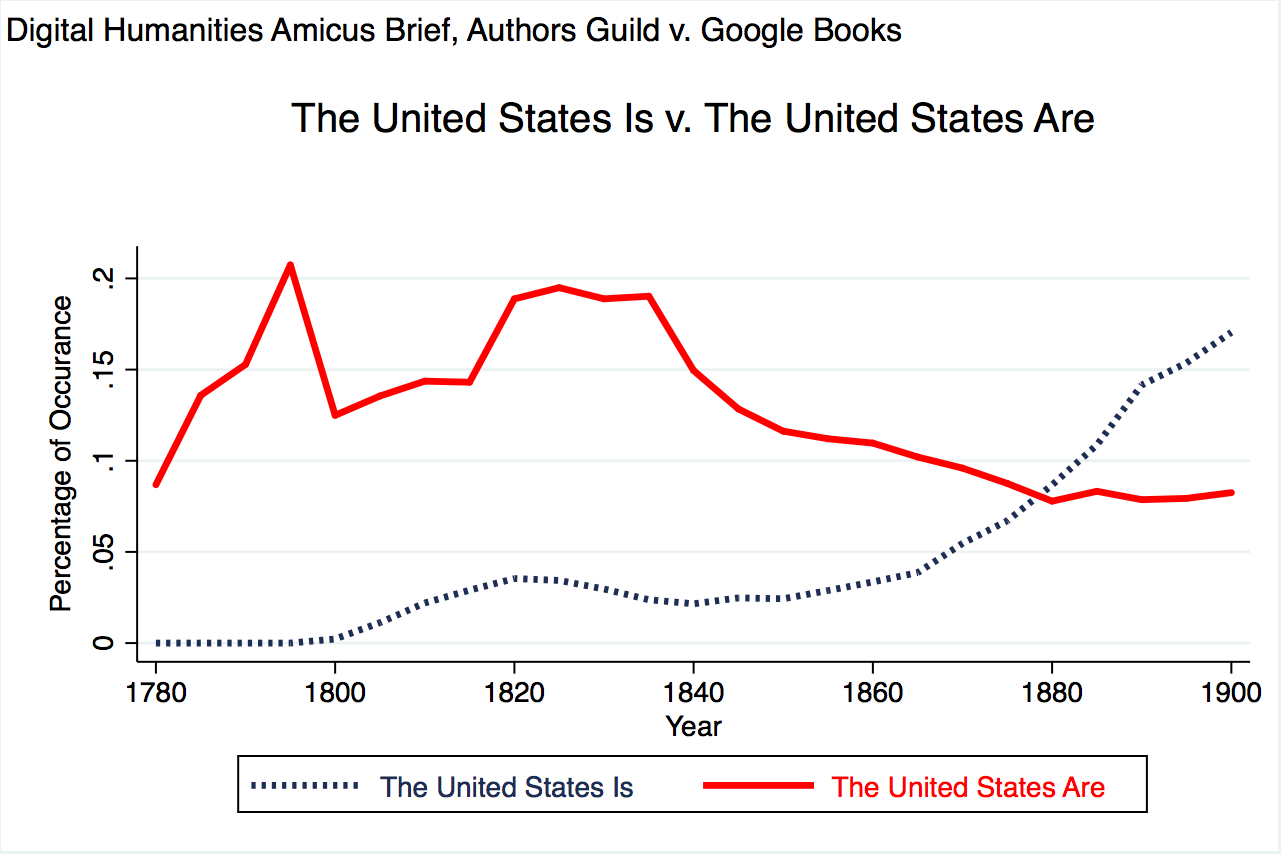

In addition to these cases, courts have also found a number of non-expressive uses to be transformative. In particular, several cases have held that automated processing and display of copyrighted photos as part of a visual search engine is a transformative and thus a fair use. In A.V. v. iParadigms, LLC, the Fourth Circuit found that the automated processing of the plaintiff students’ work in defendant’s plagiarism detection software was fair use). More recently, Authors Guild v. HathiTrust (SDNY), Authors Guild v. HathiTrust (2d Cir) and Authors Guild v. Google (SDNY) held that library digitization to create a search engine was transformative use and fair use.

Maybe we would be better off with different words for all these situations. David Nimmer suggests that in the hands of some judges, transformative use has no content at all and that it is simply synonymous with a finding of fair use. According to Pamela Samuelson, a better approach would be to distinguish transformative critiques, such as parodies, from productive uses for critical commentary. Samuelson also suggests that courts should not label orthogonal uses—uses wholly unrelated to the use made or envisaged by the original author—as transformative uses. But she does think that these are good candidates for fair use.

My personal preference would be for the term transformative use to be confined to expressive uses of copyrighted works and that non-expressive use (as exemplified by search engines, plagiarism detection software, text mining, etc) should be recognized as a distinct category of preferred use. Nonetheless, transformative use is the term of art most courts use and we should probably learn to live with it.

Further Reading

- David Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright § 13.05[A][1]

- Matthew Sag, Copyright and Copy-Reliant Technology, 103 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1607 (2009)

- Pamela Samuelson, Unbundling Fair Uses, 77 Fordham L. Rev. 2537 (2009).