I have been wanting to blog about the 7th Circuit’s appalling decision in Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation LLC, No. 13-3004 (7th Cir. Sept. 15, 2014) since I read it — exactly seven twenty minutes ago. However, two fifteen minutes ago I discovered that Prof. Rebecca Tushnet (Georgetown Law) has already said most of what I wanted to say.

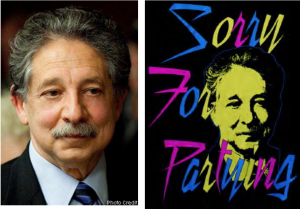

The case is about the transformative use of a photo. The case for transformation is pretty easy here because there is both substantive transformation (see below) and an obvious shift in purpose in that the original photo is a PR shot of politician opposed to a street party and the new use is a caricature of the same politician on tee-shirts and tank tops.

The court of appeals took this easy case as an opportunity to try to unsettle the law of fair use by casting stones at the concept of transformativeness. The court notes that transformativeness doesn’t appear in the statute, and says it was “mentioned” it in Campbell. What the Supreme Court actually said in Campbell was “The central purpose of this investigation is to see whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message; it asks, in other words, whether and to what extent the new work is ‘transformative.'” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 US 569 (1994). (internal citations and quotations omitted)

This is a bit more than a mention.

Now I’ll just quote Rebecca:

…Having not quoted either the Supreme Court or the Second Circuit’s definition of transformativeness (which might allow one to assess whether there is too great an overlap with the derivative works right, or for that matter with the reproduction right since that’s what the majority of Second Circuit transformativeness findings deal with), the Seventh Circuit tells us to stick to the statute. But it doesn’t tell us what the first factor does attempt to privilege and deprivilege. Instead, the court goes to its own economic lingo-driven test: “whether the contested use is a complement to the protected work (allowed) rather than a substitute for it (prohibited).” Where this appears in the statute is left as an exercise for the reader, though by placement in the opinion we might possibly infer that it is the appropriate rephrasing of factor one, as opposed to inappropriate transformativeness (though the court later says that factor one isn’t relevant at all). However, complement/substitute requires some baseline for understanding the appropriate scope of the copyright right—the markets to which copyright owners are entitled—just like transformativeness does.

The Seventh Circuit reached the right result, but its reasoning shallow, its disagreement with the Second Circuit is captious, and its wanton disregard of the jurisprudence of the last twenty years (beginning with the Supreme Court’s decision in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc) is profoundly unfortunate. These are smart judges who could have helped further develop and clarify the law, but chose not to.