I have just revised my article, IP Litigation in US District Courts: 1994 to 2014, which will be published in Volume 101 of the Iowa Law Review next year. (You can download the article from ssrn now.) This post does not attempt to summarize the full article; it focuses instead on explaining some of the more interesting graphs and data visualizations in the article.

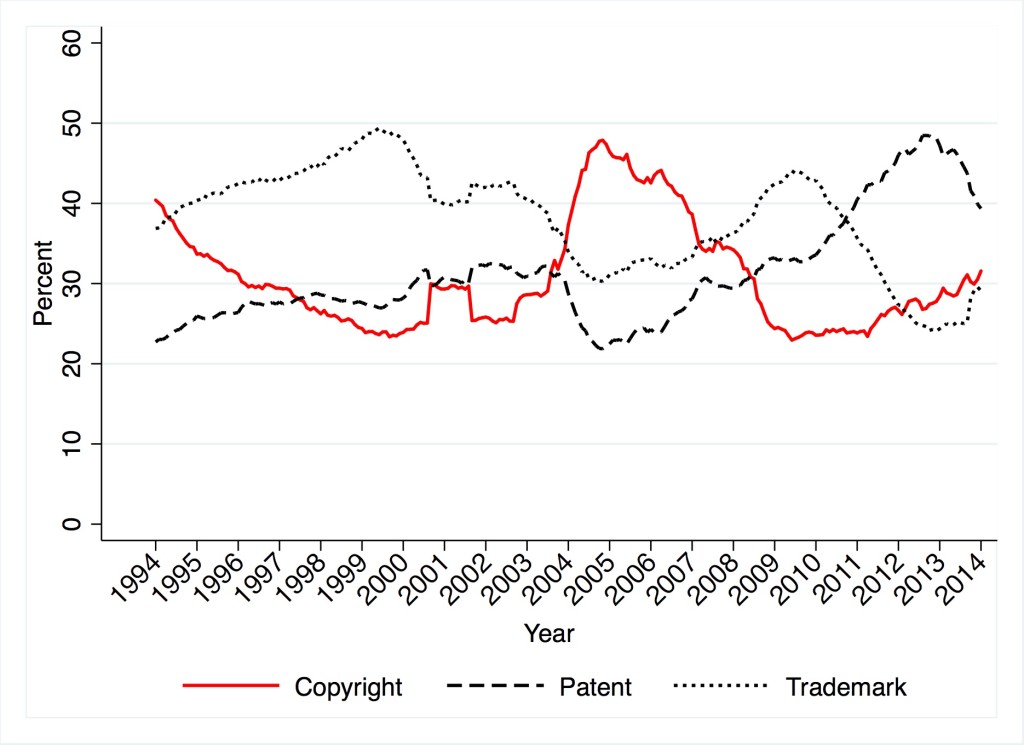

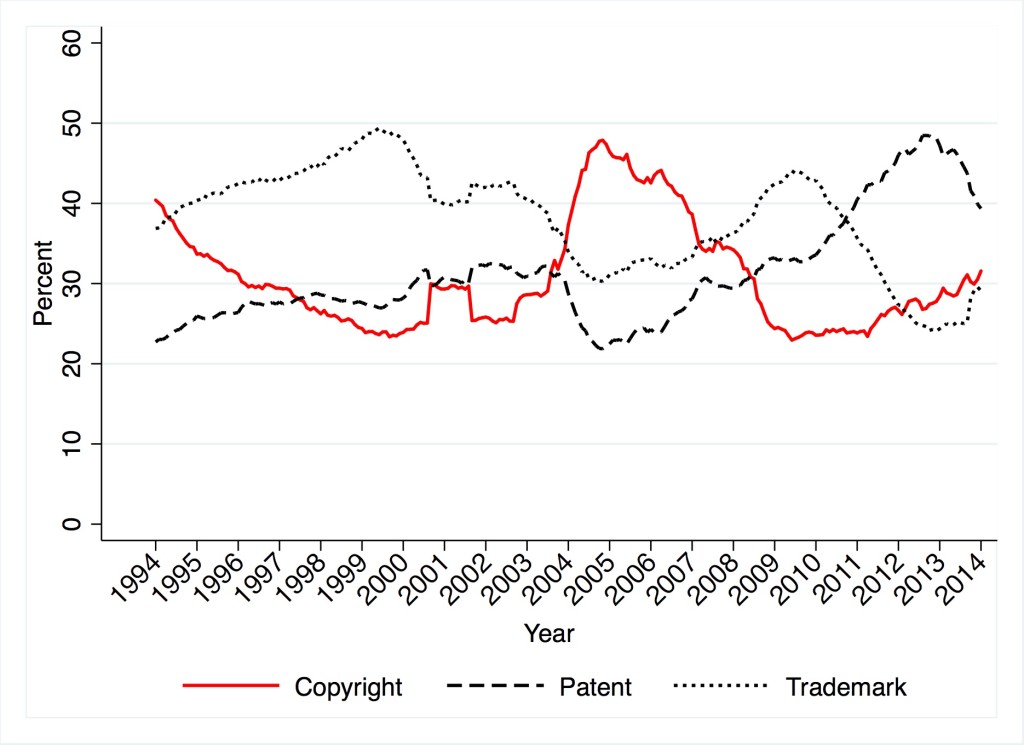

Copyright, Patent and Trademark Filings as a percentage of all IP 1994-2014

This data is presented as a 12 month moving average.

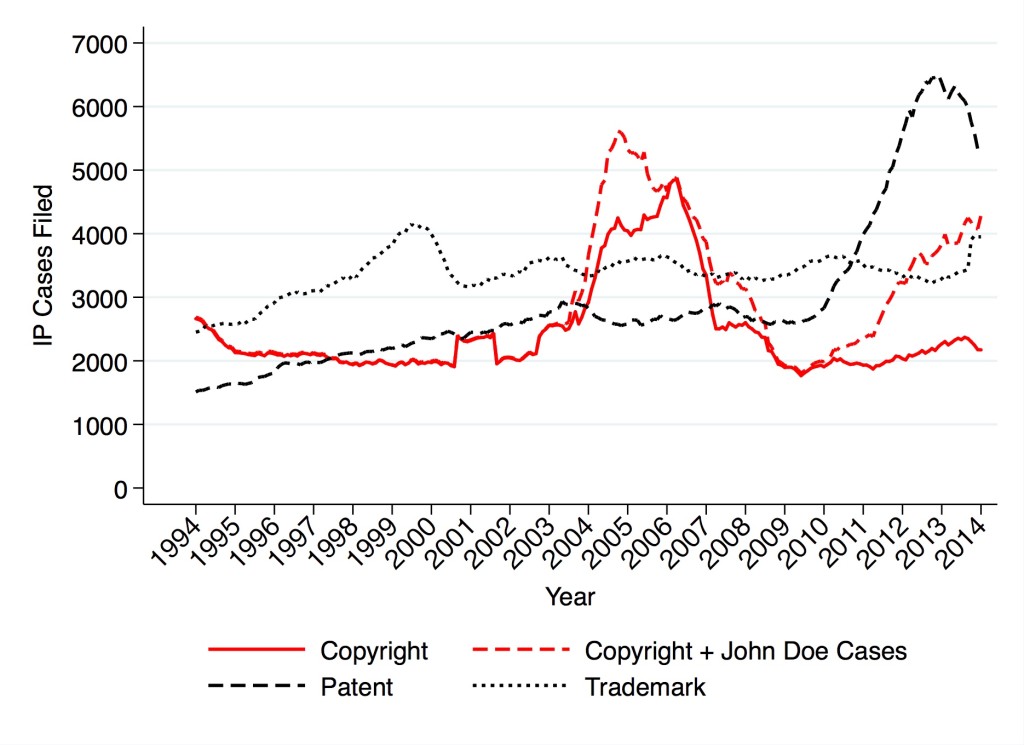

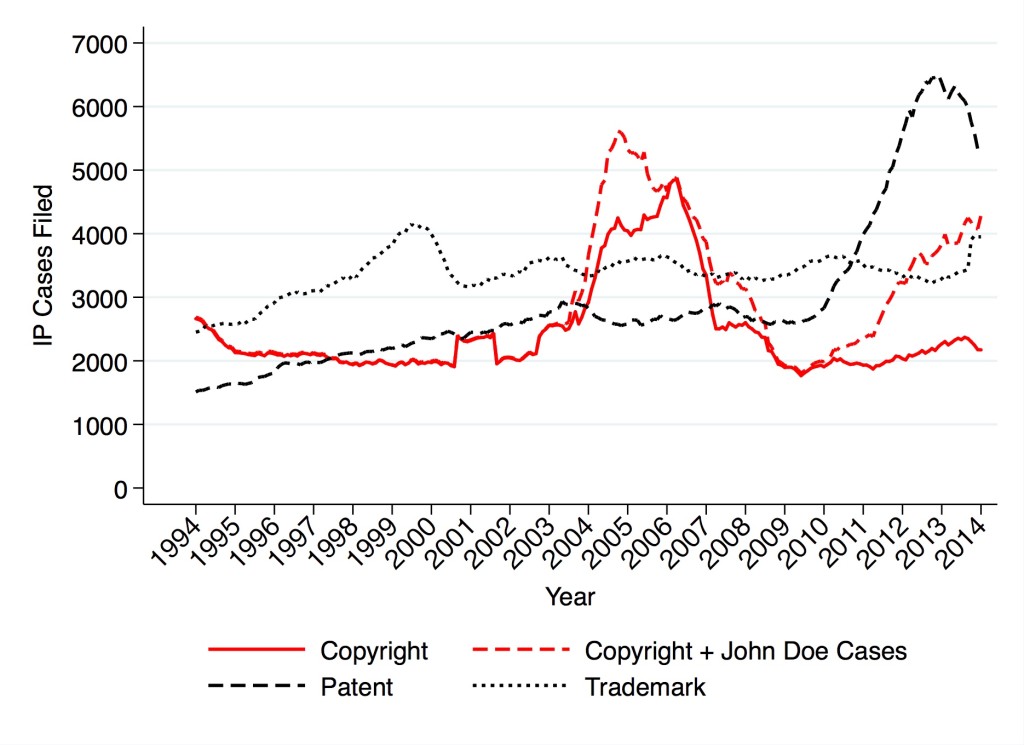

Copyright, Patent and Trademark Filings (number of cases) 1994—2014

Again, this data is presented as a 12 month moving average. The difference between the dashed redline and the solid red line clearly shows the impact of lawsuits against anonymous internet file sharers.

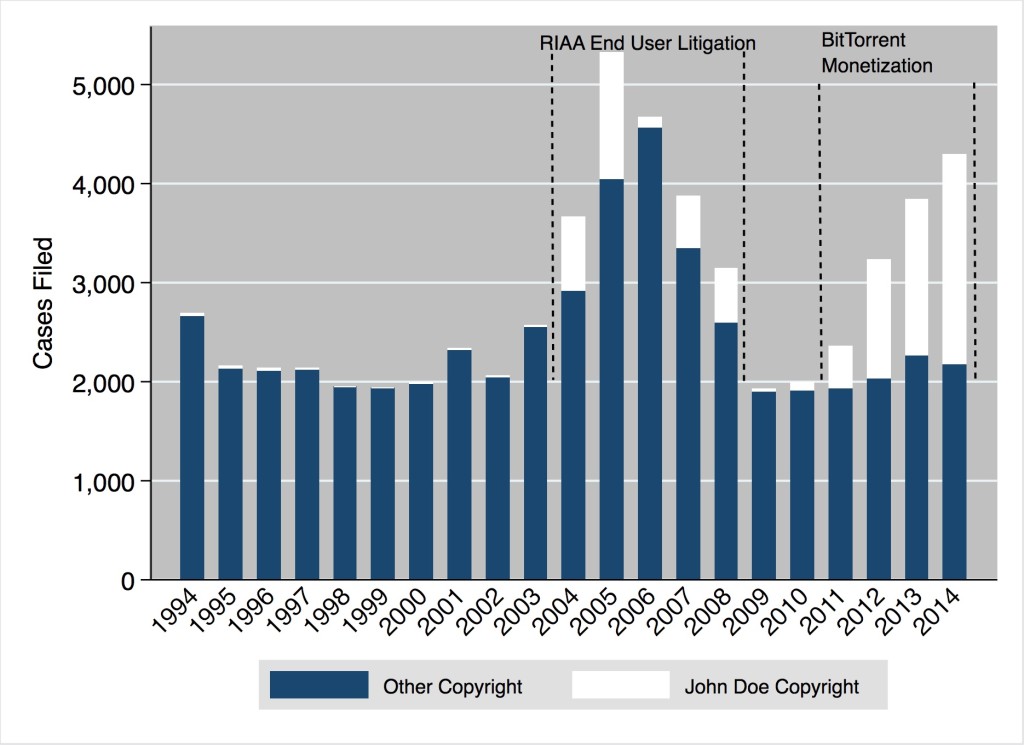

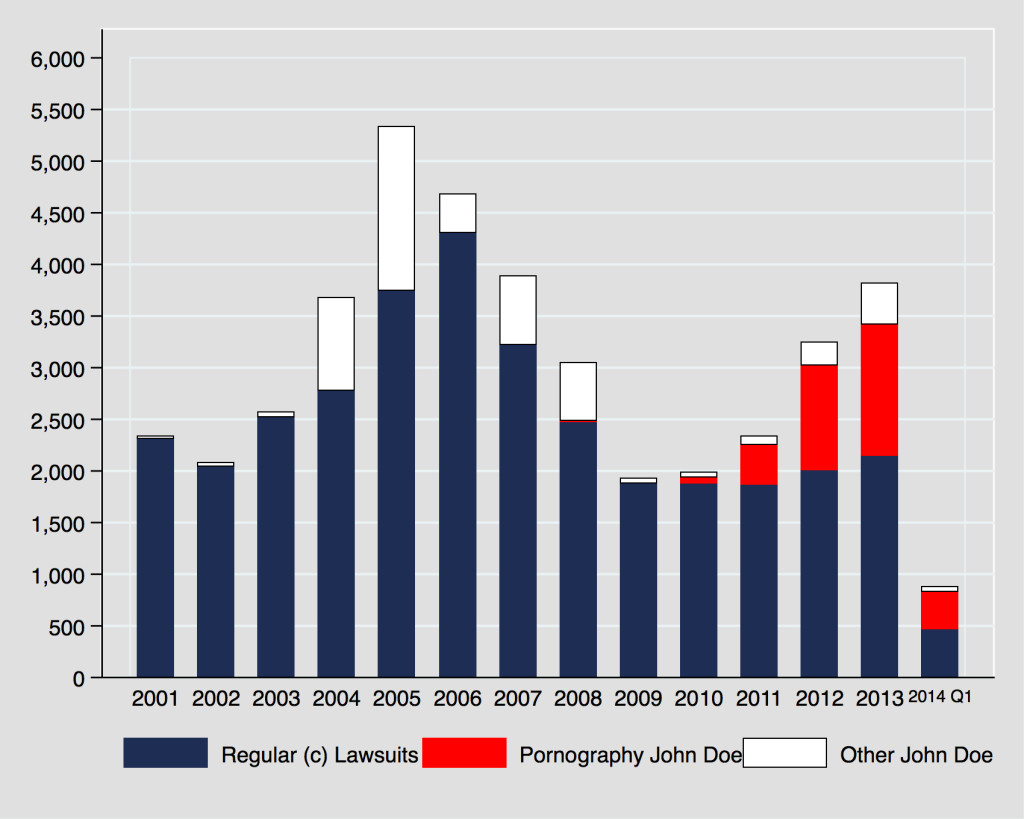

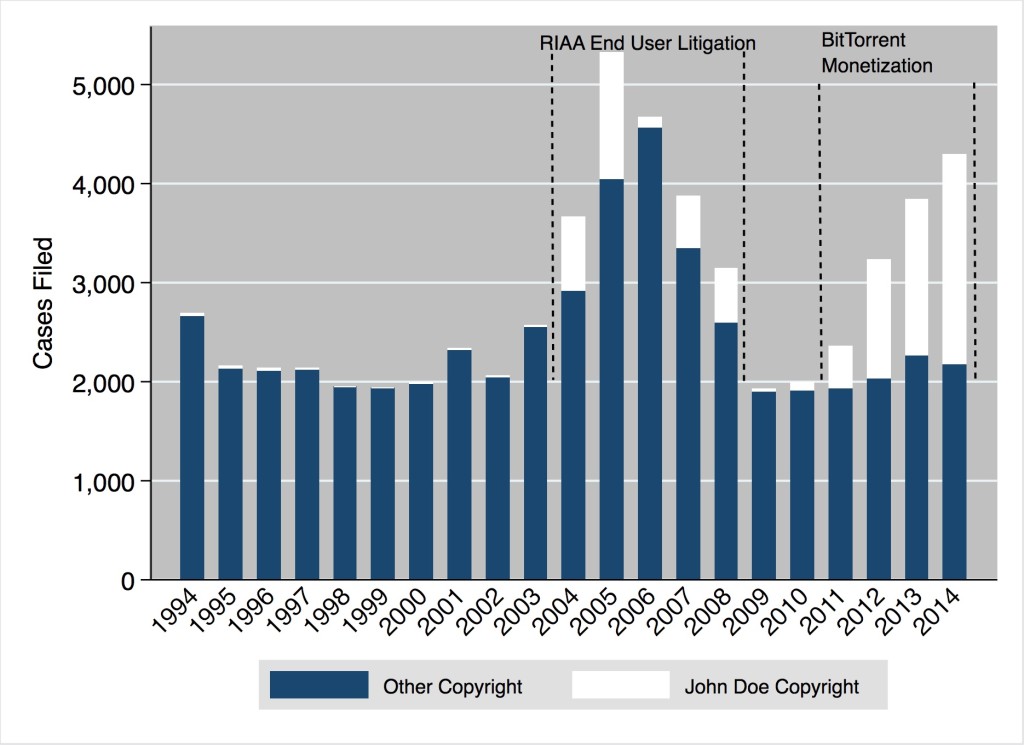

Copyright Cases 1994—2014, RIAA End-User Litigation, BitTorrent Monetization and Copyright Trolling

The impact of the current wave of copyright trolling is pretty clear.

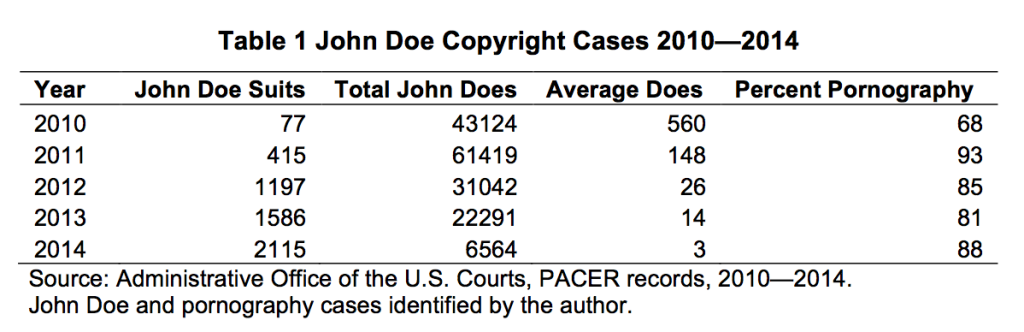

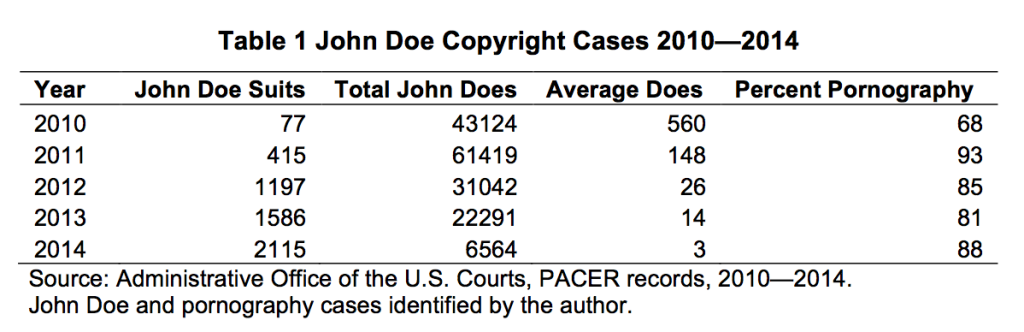

9 out of 10 of ‘copyright trolling’ cases are about pornography

As you can see from the table, the number of john does per suit has declined because courts have been far more skeptical of mass-joinder, but that has just led to more suits being filed.

One pornography company accounts for 80% of Copyright John Doe lawsuits filed in 2014 #CopyrightTrolling

In fact, the pornography producer, Malibu Media is such a prolific litigant that in 2014 it was the plaintiff in over 41.5% of all copyright suits nationwide. John Doe litigation is not a general response to Internet piracy; it is a niche entrepreneurial activity in and of itself.

[Edited at 4:17pm. The missing * for AF Holdings has been added]

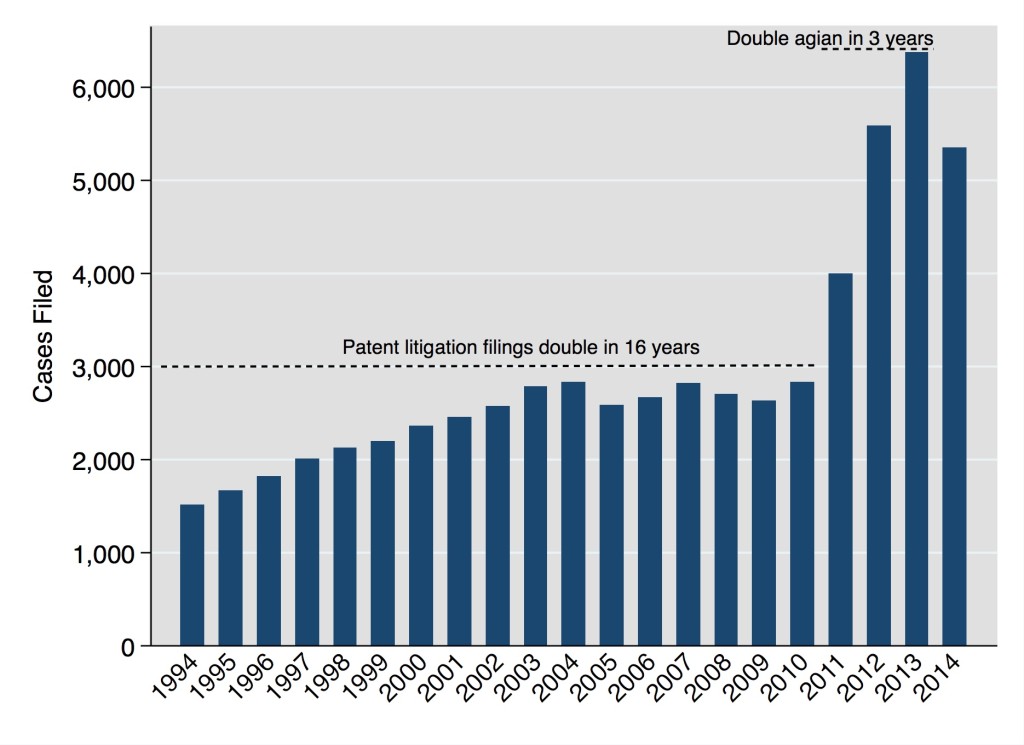

1/2 The patent litigation explosion is not exactly as it appears, compare suits filed to #defendants.

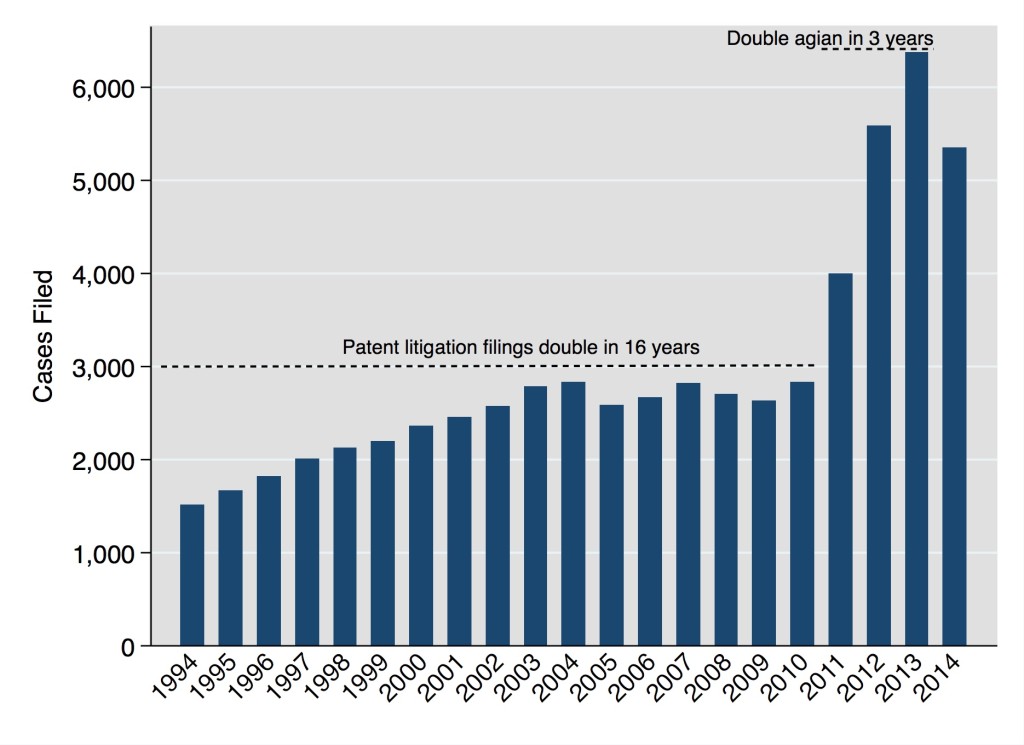

At first glance it looks like the annual volume of patent litigation in the United States doubled in the 16 years from 1994 until 2010. In the three years from 2010 to 2013 it doubled again.

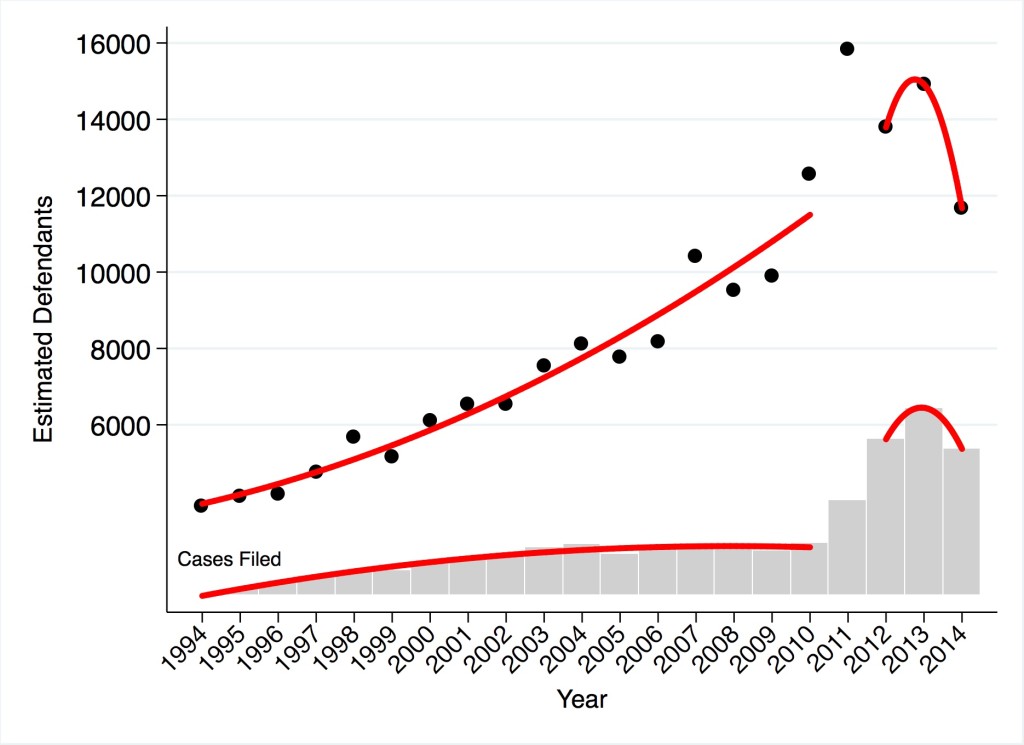

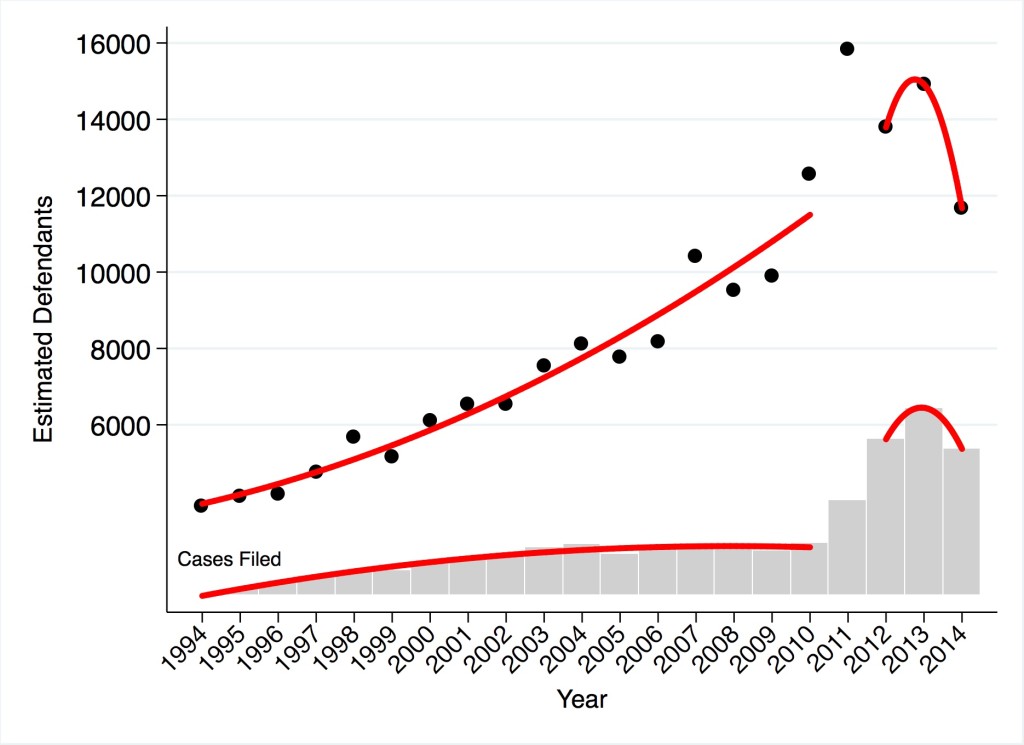

2/2 The patent litigation explosion is not exactly as it appears, compare suits filed to #defendants.

The real trend in patent litigation over the past two decades can be seen in the number of defendants filed against. The bar chart at the bottom of the next figure shows the same filing data as in the figure above. The scatter plot in the figure below shows the estimated number of defendants. Although it appears that the number of patent cases filed exploded after 2010, looking at the estimated number of defendants, it becomes clear that the period from 2010 to 2013 was more or less a continuation of the existing trend.

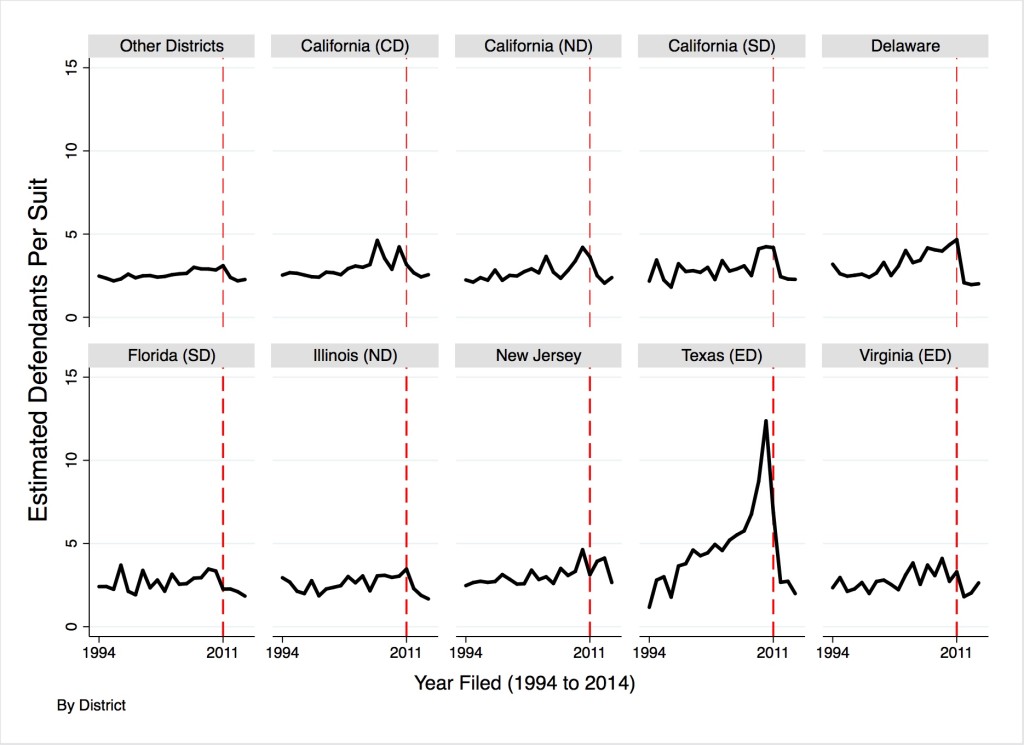

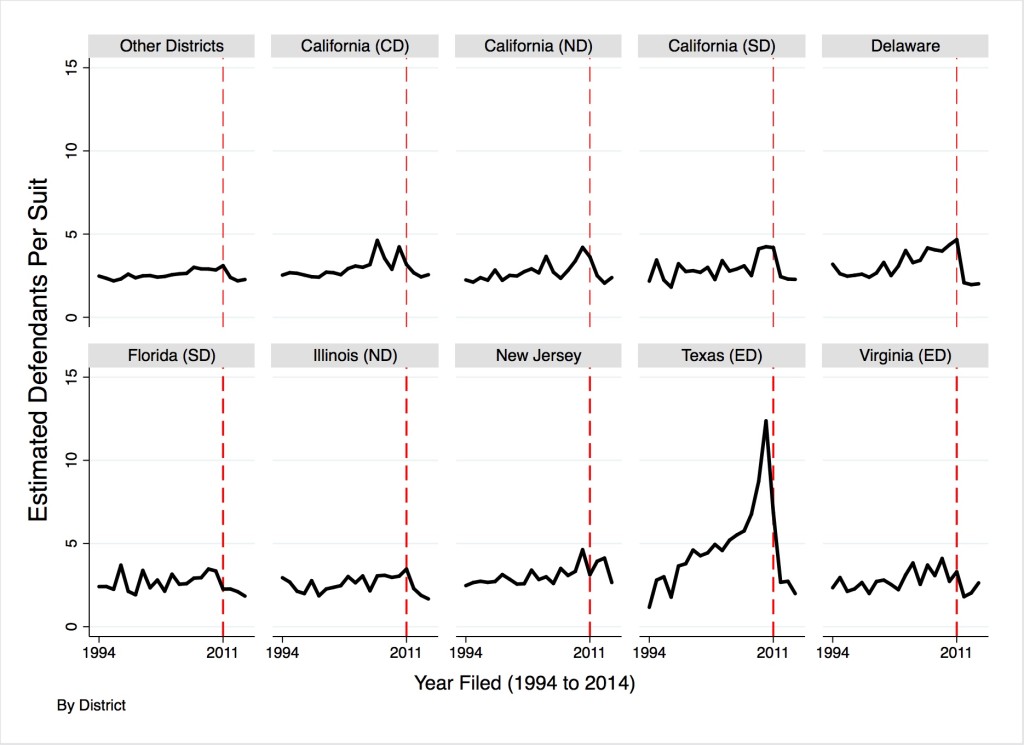

There is something wrong with the ED of Texas. Average Number of Patent Defendants per Filing 1994—2014

This figure shows the estimated number of defendants per suit for the nine most popular federal districts from 1994 to 2014 and also for an aggregation of all other districts. The vertical dashed line is set to 2011 to mark the passage of the America Invents Act. It is starkly apparent that the trend toward more defendants is greatest in the Eastern District of Texas. The estimated number of defendants in Eastern District of Texas climbs steeply from 1.66 in 1994 to 12.37 in 2010 and then drops precipitously down to 1.99 in 2014

What does all this mean? To me, it suggests that there was not exactly a “Troll Fueled Patent Litigation Explosion” between 2010 and 2012. Once you take into account the procedural changes brought into effect in 2011 by the AIA and focus on the number of defendants rather the the number of suits it seem that there was a significant troll fueled increase in the rate of patent litigation; it is just that this increase started earlier and proceeded more smoothly than the simple case filing data suggests. I refer to this revised narrative as the Troll Fueled Patent Litigation Inflation.

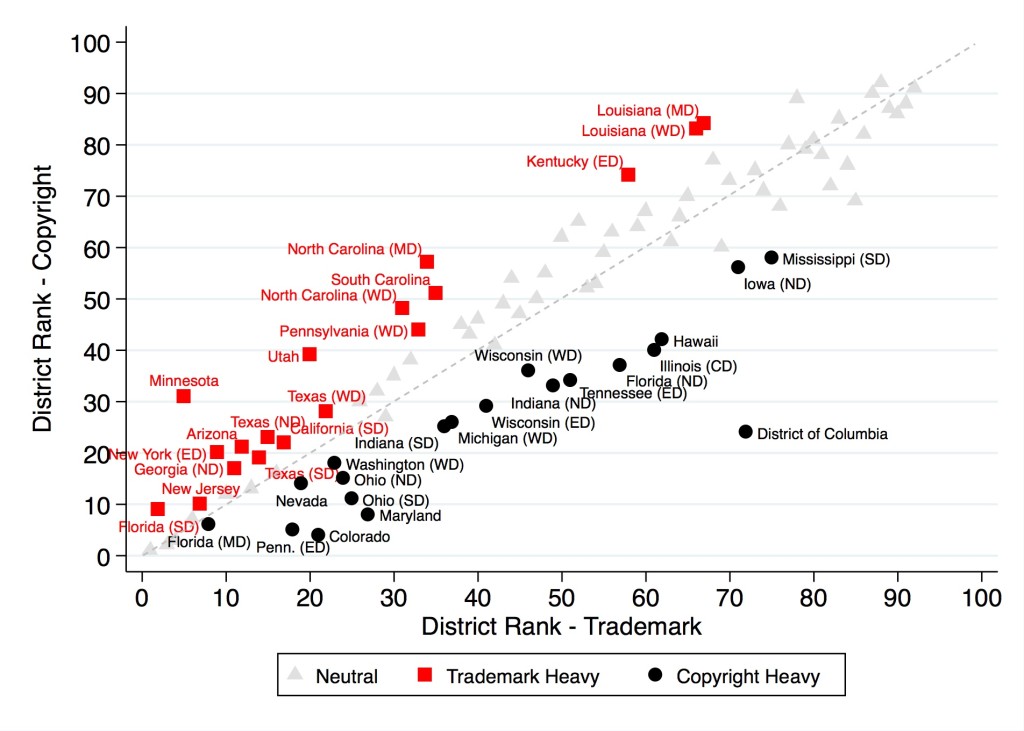

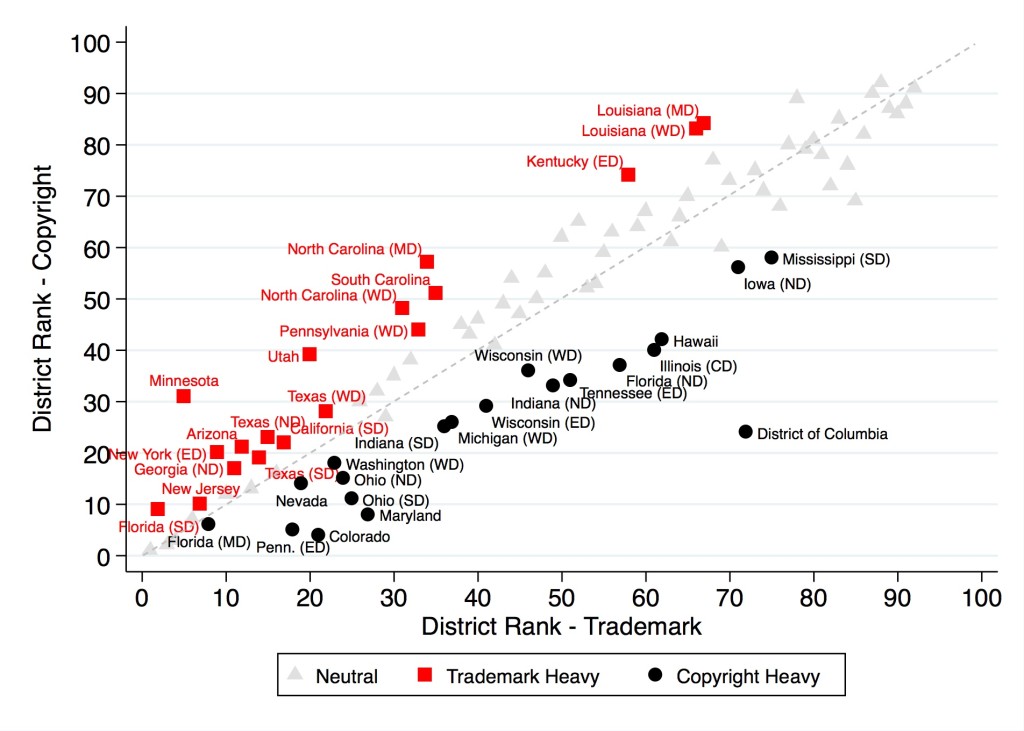

District Rankings, Copyright Compared to Trademark (2010-2014)

This figure focuses your attention on the outliers, but the general story is that copyright and trademark litigation are highly correlated at a district court level.

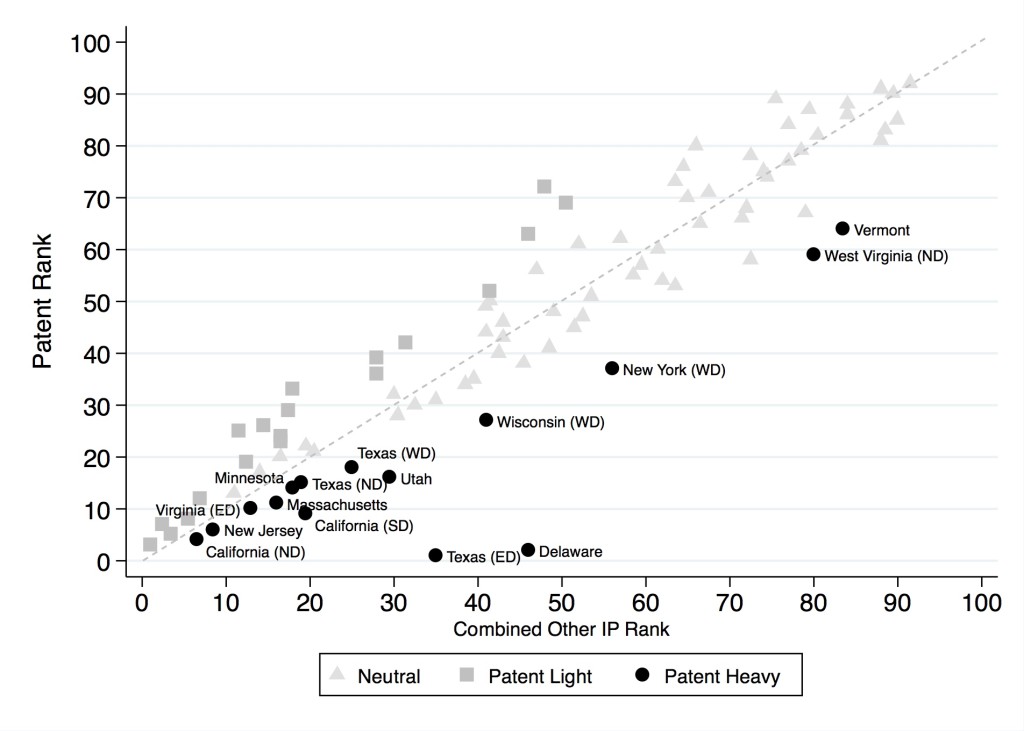

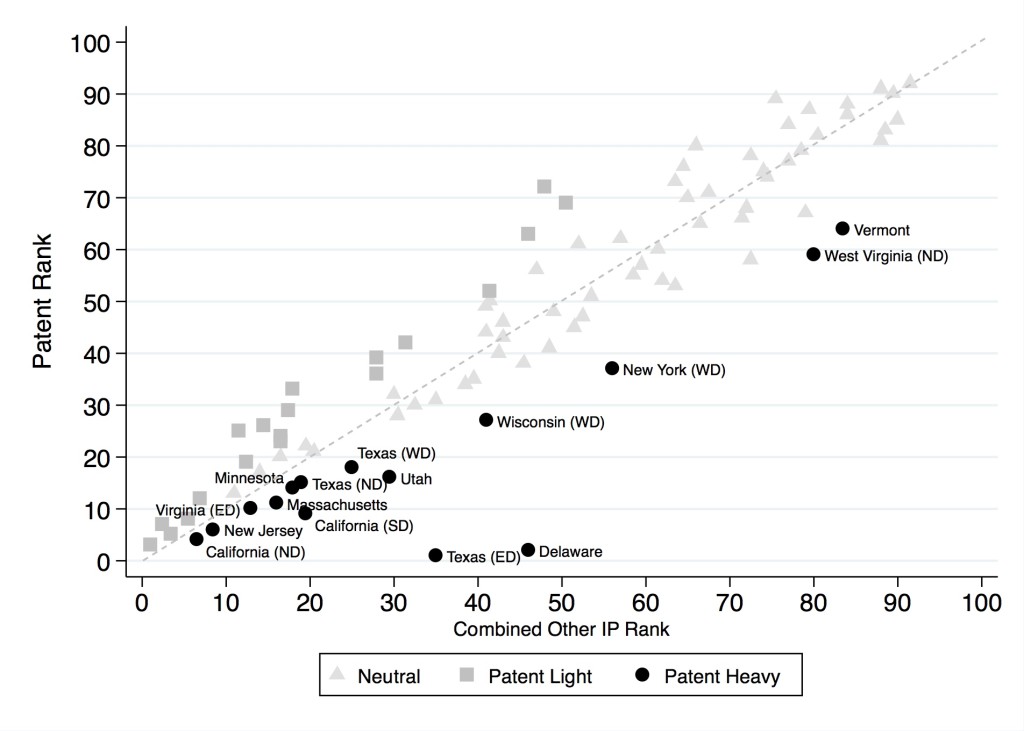

Regional Variation in Patent Litigation – Evidence of Forum Selling

The popularity of the Eastern District of Texas as a forum for patent litigation is a well-known phenomenon. However, the data and analysis presented in this study provides a new way of looking at the astonishing ascendancy of this district and the problem of form shopping in patent law more generally. The extent of forum shopping in patent law can be seen by comparing the geographic distribution of patent litigation to that of copyright and trademark. This figure illustrates District rank in terms of patent versus a combined copyright and trademark ranking for cases filed between 2010 and 2014.

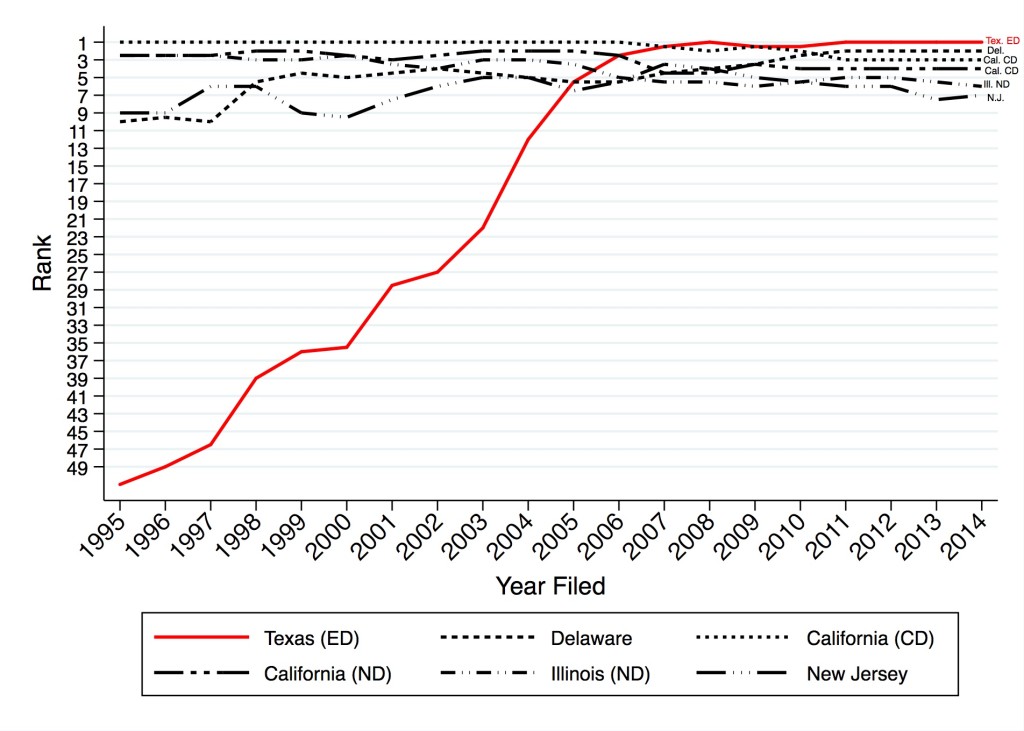

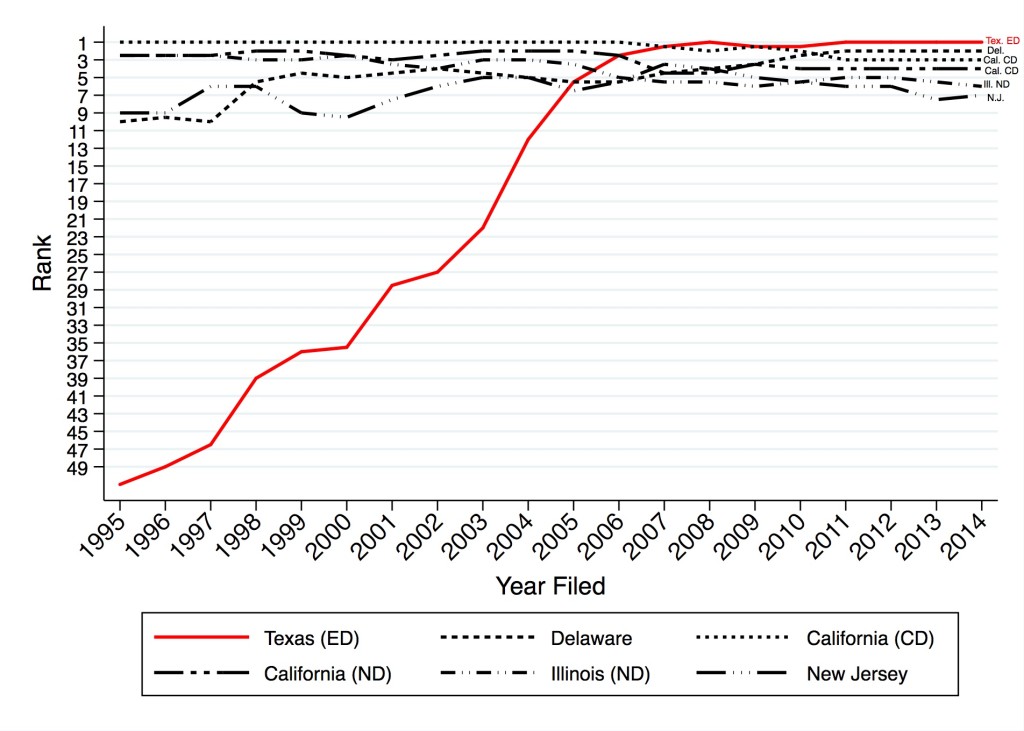

District Court Ranks for Patent Litigation 1994-2014

This is crazy!

My paper explains how we got here and summarizes the excellent work of Jonas Anderson in a new paper titled ‘Court Competition for Patent Cases‘, and Daniel Klerman and Greg Reilly in ‘Forum Selling’ each of which go into even more detail.

The first thing to note about this figure is that, but for the Eastern District of Texas and Delaware, the geographic distribution of patent litigation over the past two decades would look remarkably stable. For most of this period, the Central District of California was the most important venue for patent litigation over the last 21 years, followed by the Northern District of California. The Northern District of Illinois has also ranked consistently somewhere between second and sixth over the same period. This relative stability contrasts markedly with the steady gains made by Delaware and the remarkable ascendancy of the Eastern District of Texas between 1994 and 2014. Notice that, were it not for the Eastern District of Texas, the scale on Figure 11 would range from 10 to 1, rather than 50 to 1. Framed accordingly, the steady ascent of Delaware from 9th in 1994 to 2nd from 2011 to the present day would be more noteworthy. However, the rise of the Eastern District of Texas from literal obscurity—it only saw 8 patent cases in 1994—to preeminence over the same period dwarfs all other changes.