Authors Guild v. Google: library digitization as fair use vindicated, again.

After more than eight years of litigation, the legality of the Google Books Search engine has finally been vindicated.

Authors Guild v Google Summary Judgement (Nov. 14, 2013)

The heart of the decision

The key to understanding Authors Guild v. Google is not in the court’s explanation of any of the individual fair use factors — although there is a great deal here for copyright lawyers to mull over — but rather in the court’s description of its overall assessment of how the statutory factors should be weighed together in light of the purposes of copyright law.

“In my view, Google Books provides significant public benefits. It advances the progress of the arts and sciences, while maintaining respectful consideration for the rights of authors and other creative individuals, and without adversely impacting the rights of copyright holders. It has become an invaluable research tool that permits students, teachers, librarians, and others to more efficiently identify and locate books. It has given scholars the ability, for the first time, to conduct full-text searches of tens of millions of books. It preserves books, in particular out-of-print and old books that have been forgotten in the bowels of libraries, and it gives them new life. It facilitates access to books for print-disabled and remote or underserved populations. It generates new audiences and creates new sources of income for authors and publishers. Indeed, all society benefits.” (Authors Guild v. Google, p.26)

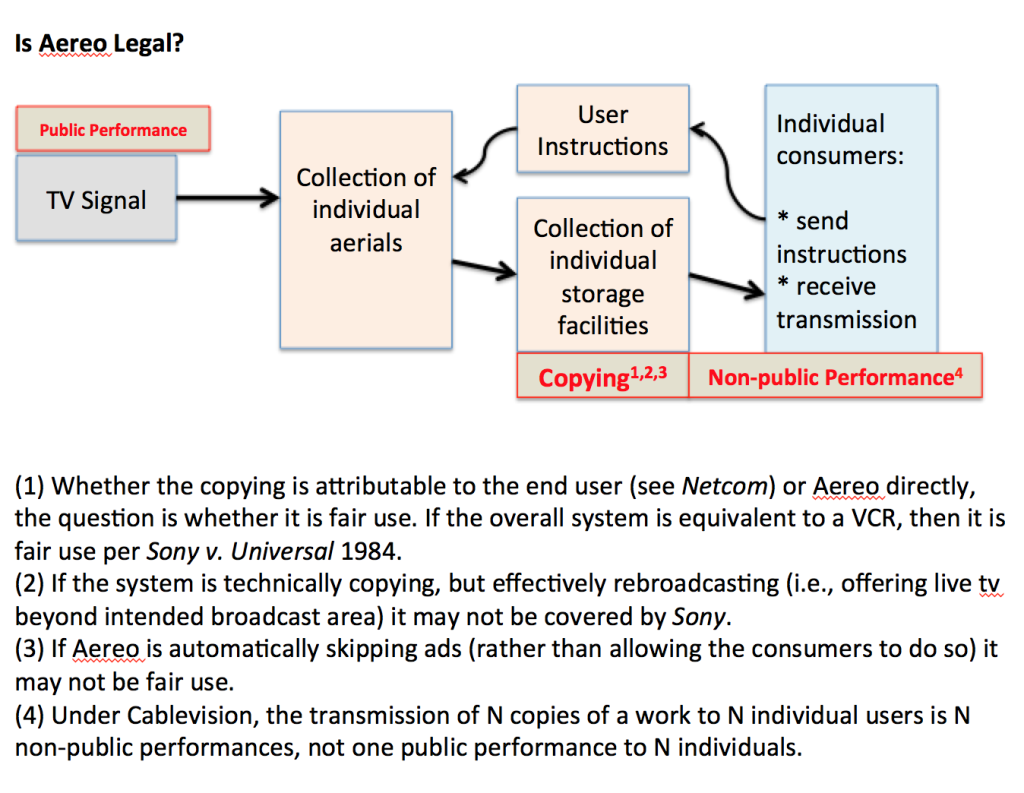

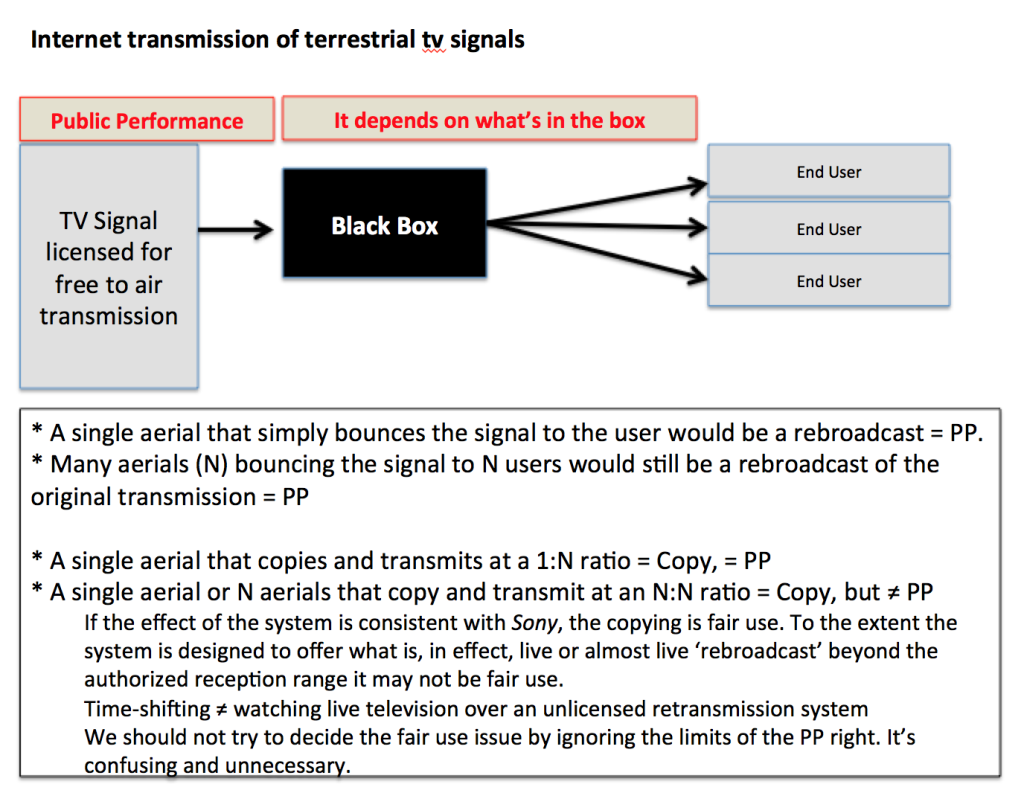

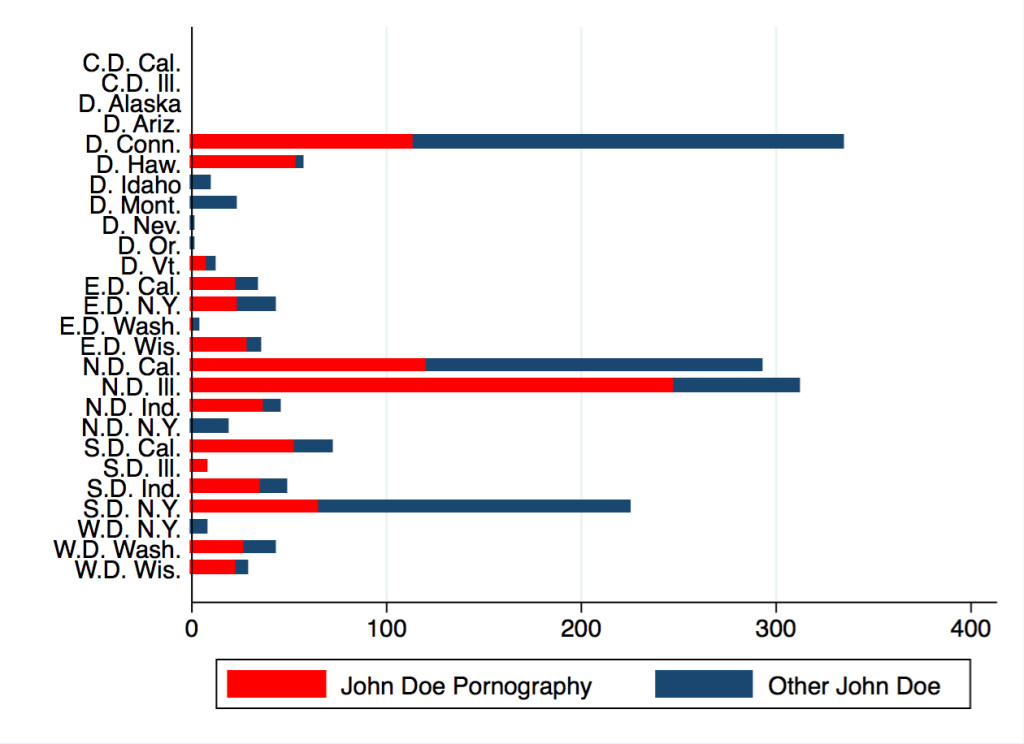

Even before last year’s HathiTrust decision (Authors Guild v. Hathitrust), the case law on transformative use and market effect was stacked in Google’s favor. Nonetheless, Judge Chin’s rulings in other cases (e.g. WNET, THIRTEEN v. Aereo, Inc.) suggest that he takes the rights of copyright owners very seriously and that it was essential to persuade him that Google was not merely evading the rights of authors through clever legal or technological structures. The court’s conclusion that the Google Library Project “advance[d] the progress of the arts and sciences, while maintaining respectful consideration for the rights of authors and other creative individuals, and without adversely impacting the rights of copyright holders” pervades all of its more specific analysis.

Data mining, text mining and digital humanities

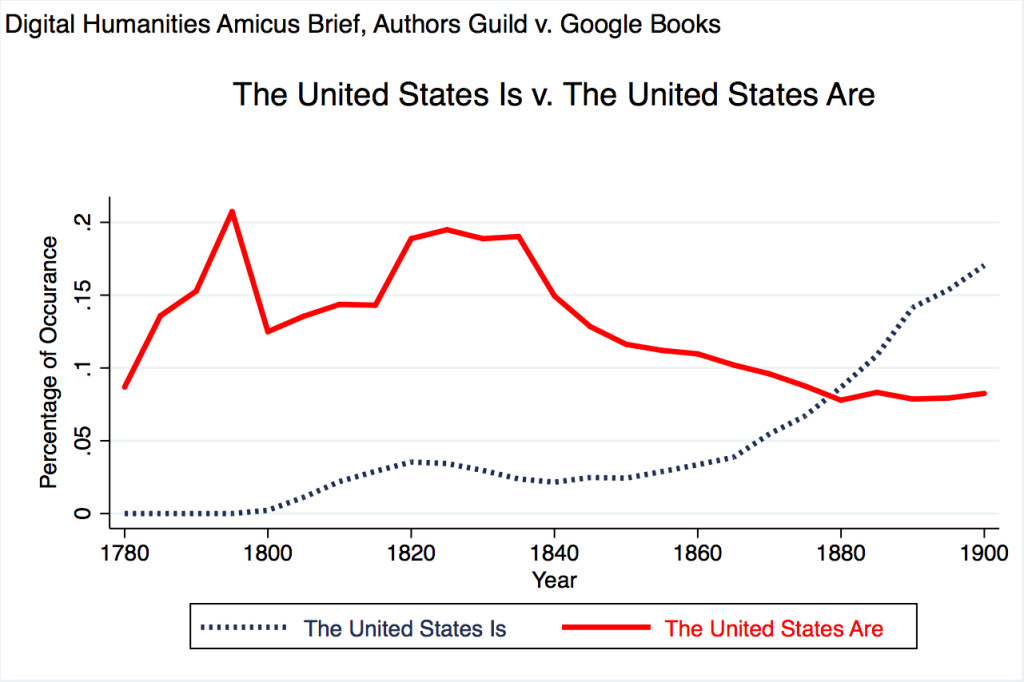

An entire page of the judgment is devoted to explaining how digitization enables data mining. This discussion relies substantially on the Amicus Brief brief of Digital Humanities and Law Scholars signed by over 100 academics last year.

“Second, in addition to being an important reference tool, Google Books greatly promotes a type of research referred to as “data mining” or “text mining.” (Br. of Digital Humanities and Law Scholars as Amici Curiae at 1 (Doc. No. 1052)). Google Books permits humanities scholars to analyze massive amounts of data — the literary record created by a collection of tens of millions of books. Researchers can examine word frequencies, syntactic patterns, and thematic markers to consider how literary style has changed over time. …

Using Google Books, for example, researchers can track the frequency of references to the United States as a single entity (“the United States is”) versus references to the United States in the plural (“the United States are”) and how that usage has changed over time. (Id. at 7). The ability to determine how often different words or phrases appear in books at different times “can provide insights about fields as diverse as lexicography, the evolution of grammar, collective memory, the adoption of technology, the pursuit of fame, censorship, and historical epidemiology.” Jean-Baptiste Michel et al., Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books, 331 Science 176, 176 (2011) (Clancy Decl. Ex. H)” (Authors Guild v. Google, p.9-10)

The court held that Google Books was “[transformative] in the sense that it has transformed books text into data for purposes of substandard research, including data mining and text mining in new areas, thereby opening up new fields of research. Words in books are being used in a way they have not been used before. Google books has created something new in the use of text — the frequency of words and trends in the usage provide substantial information.”

A snippet of new law

Last year, the court in HathiTrust ruled that library digitization for the non-expressive use of text mining and the expressive use of providing access to the visually disabled was fair use. Today’s decision in Authors Guild v. Google supports both of those conclusions; it further holds that the use of snippets of text in search results is also fair use. The court noted that displaying snippets of text as search results is similar to the display of thumbnail images of photographs as search results and that these snippets may help users locate books and determine whether they may be of interest.

The judgment clarifies something that confuses a lot of people — the difference between “snippet” views on Google books and more extensive document previews. Google has scanned over 20 million library books to create its search engine, mostly without permission. However, Google has agreements with thousands of publishers and authors who authorize it to make far more extensive displays of their works – presumably because these authors and publishers understand that even greater exposure on Google Books will further drive sales.

The court was not convinced that Google Books poses any threat of expressive substitution because, although it is a powerful tool for learning about books individually and collectively, “it is not a tool to be used to read books.”

The Authors Guild had attempted to show that an accumulation of individual snippets could substitute for books, but the court found otherwise: the kind of accumulation of snippets that the plaintiffs were suggesting was both technically infeasible because of certain security measures and, perhaps more importantly, was bizarre and unlikely: “Nor is it likely that someone would take the time and energy to input countless searches to try and get enough snippets to comprise an entire book. Not only is that not possible as certain pages and snippets are blacklisted, the individual would have to have a copy of the book in his possession already to be able to piece the different snippets together in coherent fashion.”

Significance

Today’s decision is an important victory for Google and the entire United States technology sector; it also confirms the recent victory libraries, academics and the visually disabled in Authors Guild v. HathiTrust.

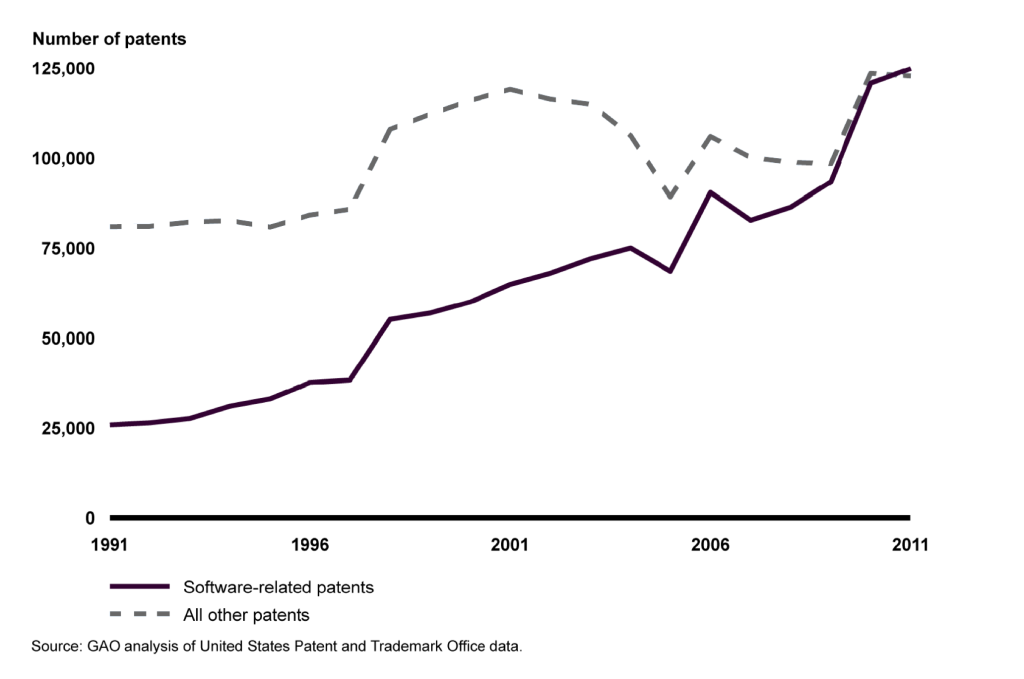

Unless today’s decision is overruled by the Second Circuit or the Supreme Court — something I personally think is very unlikely –, it is now absolutely clear that technical acts of reproduction that facilitate purely non-expressive uses of copyrighted works such as books, manuscripts and webpages do not infringe United States copyright law. This means that copy-reliant technologies including plagiarism detection software, caching, search engines and data mining more generally now stand on solid legal ground in the United States. Copyright law in the majority of other nations does not provide the same kind of flexibility for new technology.

All in all, an excellent result.

* Updated at 4.57pm. The initial draft of this post contained several dictation errors which I will now endeavor to correct. My apologies. Updated at 5.17pm with additional links and minor edits.