A pattern of “brazen misconduct and relentless fraud”

Like many, I took great satisfaction from reading that John L Steele had plead guilty and acknowledged his role in the “copyright trolling” scheme that took in millions of dollars in settlements from 2010 to 2012.

For a short while, the lawyers at Prenda–Paul Duffy,John L. Steele and Paul R. Hansmeier–were the public face of copyright trolling. According to the courts, Duffy, Steele and Hansmeier engaged in “vexatious litigation designed to coerce settlement” in a pattern of “brazen misconduct and relentless fraud.” They lied to the courts, forged documents, practiced identity theft, placed their own content online so that they could sue people for stealing it, and generally behaved badly.

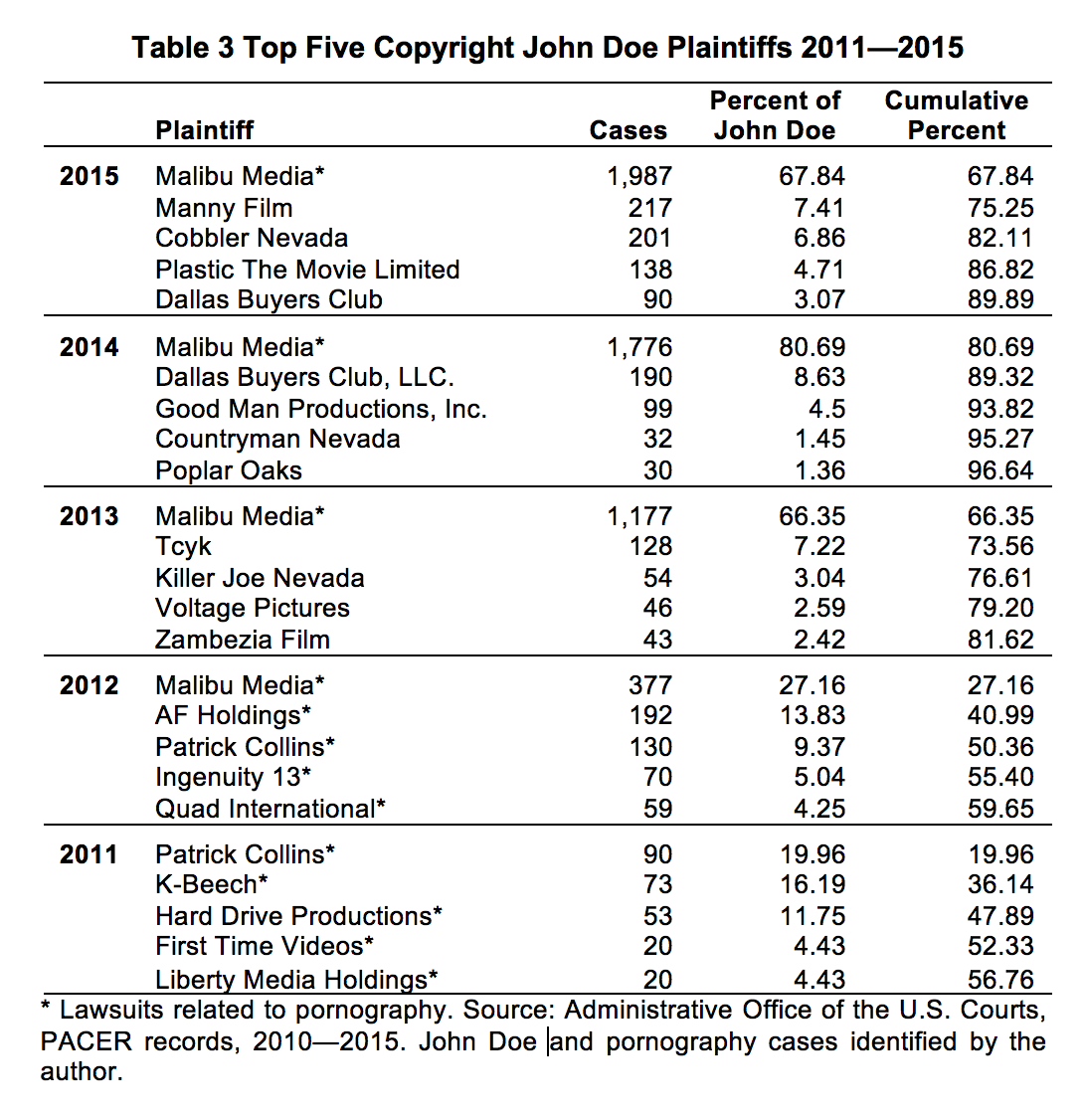

The scheme worked as follows: lawyers would file copyright suits alleging that some unknown person (John Doe) identified only by their IP address had infringed copyright by using BitTorrent, an online file sharing protocol. The laywers would file a case against “John Does 1- 1000” and pursuade the court to let them subpoena ISPs to get the subscriber details that matched those IP addresses. They would threaten those newly unmasked John Does and demand payment to drop the suit. Otherwise, Does alleged pornography viewing habits would be exposed to the world and he would probably end up paying tens of thousands in statutory damages.

Prenda is gone, but copyright trolling continues

Duffy died in 2015. Steele and Hansmeier were placed under federal indictment in December 2016 for “an elaborate scheme to fraudulently obtain millions of dollars in copyright lawsuit settlements by deceiving state and federal courts throughout the country.” And now that Steele has plead guilty to those charges, Hansmeier’s conviction seems like a certainty.

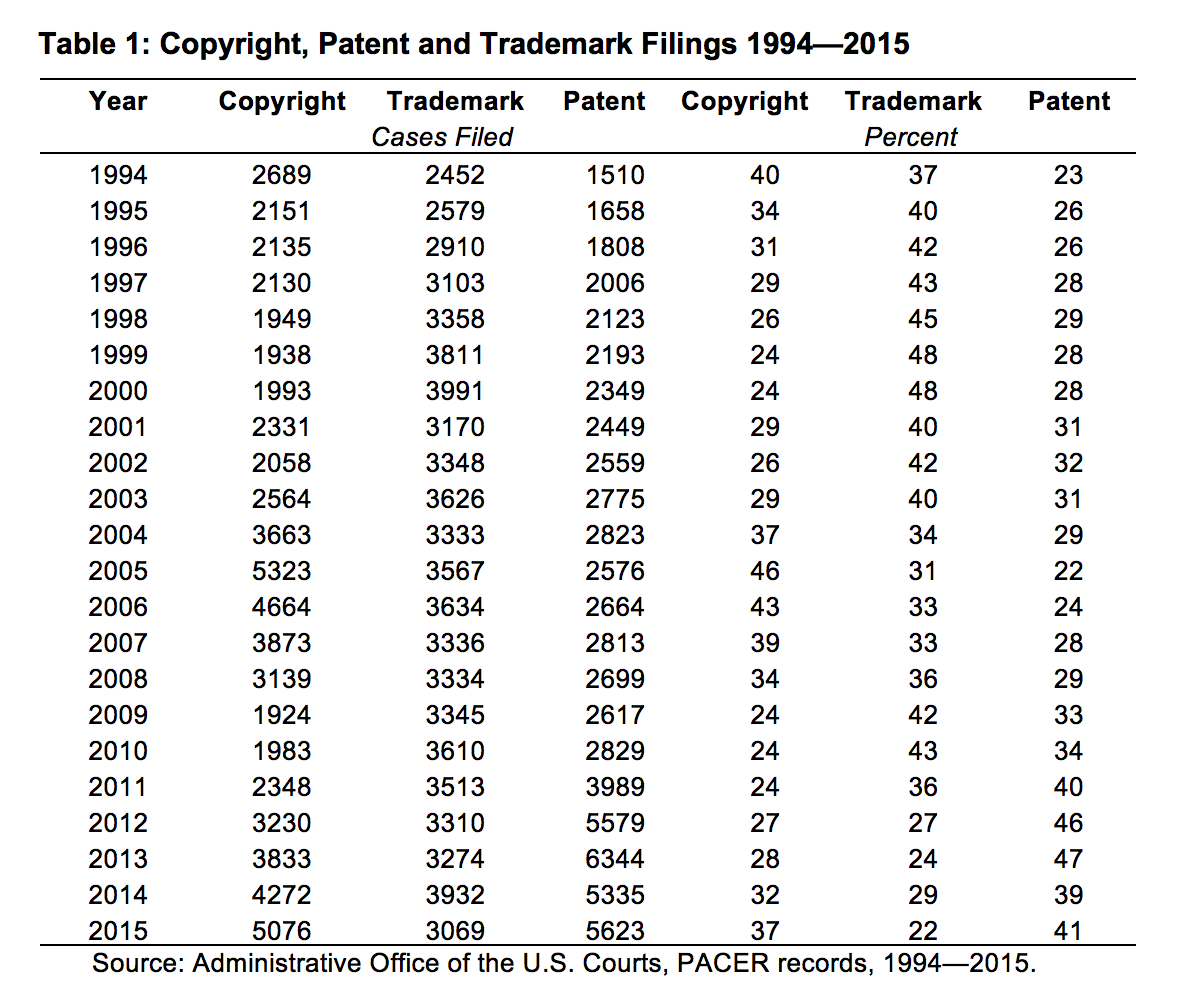

It is satisfying to see justice finally catch up with Steele and Hansmeier, but anyone who thinks that this is the end of copyright trolling has not been paying attention. In fact, other than a brief hiccup in early 2016, the filing of lawsuits designed to extract settlements from alleged online pirates has only increased since Prenda went out of business.

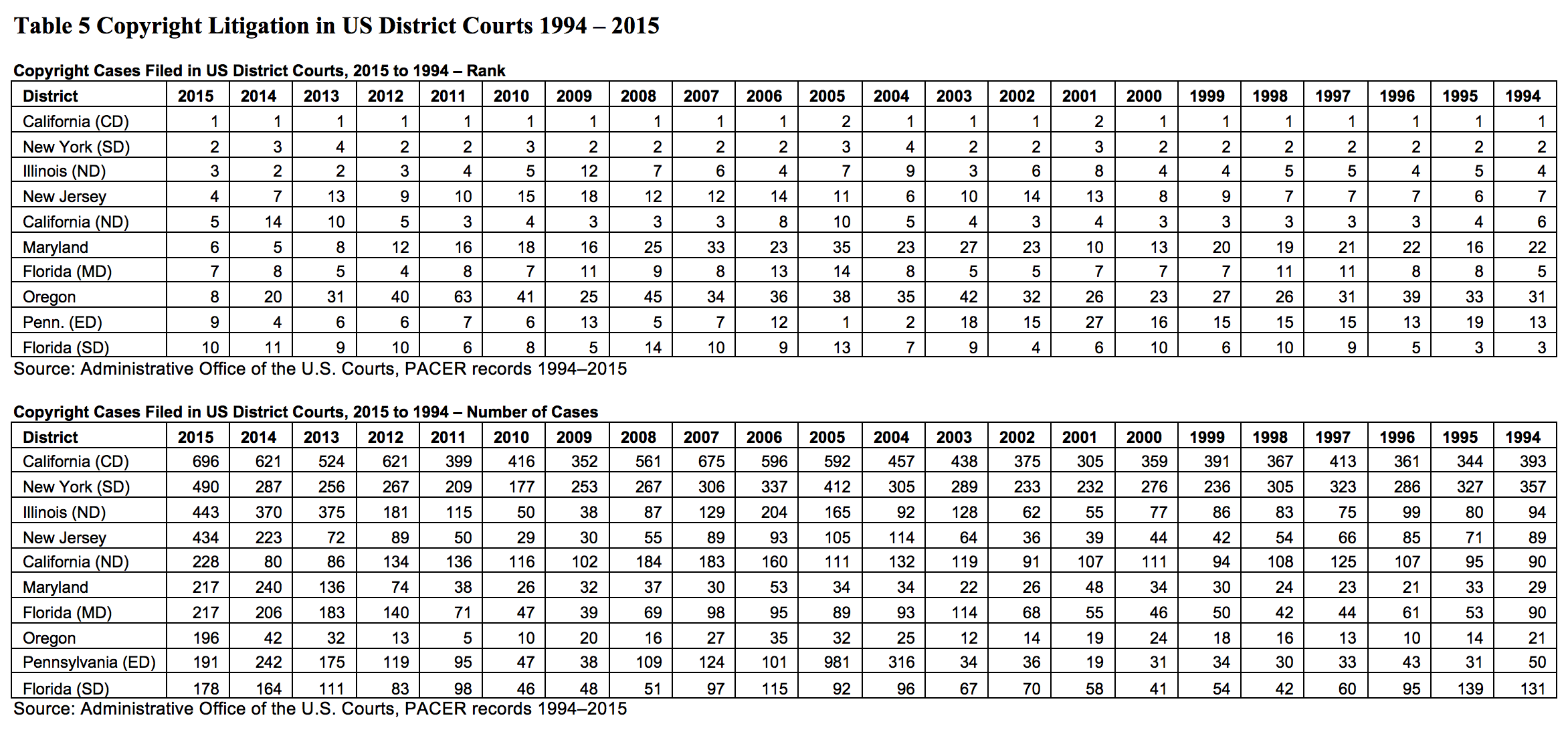

As my co-author, Jake Haskell, and I will show in a paper to be made public next week (we are proofreading right now), in the post-Prenda era, lawsuits filed against John Doe defendant made up more than 52% of all copyright cases in in the United States in 2014 and 58% in 2015. The number of suits dropped slightly after Malibu Media lost a case on summary judgment in January 2016, but the rate of filing is increasing again. Even so, between 2014 and 2016 copyright trolling accounted for 49.8% of the federal copyright docket.

Our analysis of the federal court filing records indicates that in 2016, the average number of defendants in each of the John Doe cases was 4.7 on a conservative estimate . In other words, although there were 1,362 John Doe copyright cases filed last year, 6,483 individual defendants were targeted. Without doubt, some of those people were illegally downloading movies, but a great many were not.

The new breed of plaintiffs who filled Prenda’s shoes are different to Prenda, but not different enough. The plaintiffs’ claims of infringement still rely on poorly substantiated form pleading and are targeted indiscriminately at non-infringers as well as infringers. Plaintiffs have realized that there is no need to invest in a case that could actually be proven in court, or in forensic systems that reliably identify infringement without a large ratio of false positives. Their lawsuits are filed primarily to generate a list of targets for collection; and are unlikely-in our view-to withstand the scrutiny of contested litigation.

The human cost of copyright trolling is significant. It is true that sometimes the plaintiffs get lucky and target an actual infringer who is motivated to settle. But even when the infringement has not occurred or where the infringer has been misidentified, some combination of the threat of statutory damages of up to $150,000 for a single download, tough talk, and technological doublespeak are usually enough to intimidate even innocent defendants into settling.

In our paper, titled “Defense Against the Dark Arts of Copyright Trolling” (available on ssrn.com next week, if all goes to plan), we undertake a detailed analysis of the legal and factual underpinnings of these online file sharing cases against John Doe defendants. We analyze the weaknesses of the typical plaintiff’s case and integrate that analysis into a comprehensive strategy roadmap for defense lawyers and pro se defendants. In short, as our title suggests, we aim provide a comprehensive and useful guide to the defense against the dark arts of copyright trolling.